from echo-chamber to eco-systems: museums for a vanishing world

part two of 'Art and Intent', an anthology of personal encounters and what I've learnt from them

‘Naval’ by Yann Tiersen (click to play as part of the reading experience)

In November 2020 when the doors of the world were briefly ajar between lockdowns, I came across a magnificent review of a British Museum exhibition. Laura Cumming’s ‘Arctic: Culture and Climate - visions of a vanishing world’ opens like this:

‘There is a vision, in this magnificent show, of the strange hinterland where Arctic ice melts into the snow-covered ocean. There is no obvious distinction, indeed the water’s edge is all but invisible.’

Evocatively, this ‘vision’ gradually reveals itself as a meta-moment, accurately conjuring the very experience of entering the exhibition:

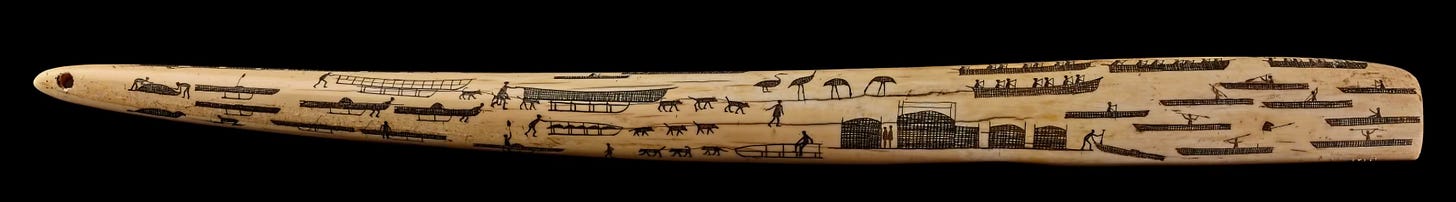

‘What you see is a series of dark boats drawn on sledges across a white plane dotted with walruses and long-legged birds.’

And then you read that:

‘All the images are inky black, exquisitely carved into the tusk of one such walrus, caught on exactly this kind of boat. Its ivory is beautifully used to stand in for the all-encompassing Arctic whiteout’.

And suddenly you realise that the 3D visual narrative you’ve entered, firstly by reading the review, and then by stepping into the exhibition space, has in fact been - symbolically, unknowingly - immortalised by the hand of ‘Happy Jack’, sometime in the early 20th century; one of numerous Arctic artists of ivory, of ice, of snow, of white sea salt and cubed pink flesh of whale, of seal skin scraped to translucent silver, for manufacture into practical gear. Artists unknown outside of their ‘circle’.

There are fragments of ancient bone jewellery, discovered in newly thawed ice; sculpted figures of reindeer and caribou so sinuously streamlined as to be almost abstract. There are needles made of walrus bone and monuments of balanced stones, a kind of ancestral land art that abides for centuries, marking memories or indicating reindeer paths through the wilds.

You can take the British Museum 360' virtual exhibition tour, with interesting rationale and curation details. You can watch, animated, the shrinking of the polar ice cap since the 1970s, just as it was projected underfoot at the entrance to the exhibition, making it feel as if, by stepping in, you personally triggered the ice to melt. You can explore a gallery of mini-documentaries delving into the climate change, sustainability and cultural anthropology themes of the event. You will come across over 40 indigenous cultures crowning the Arctic, and the linguistic diversity of even more dialects. And you will learn of the resourcefulness, resilience and creativity of threatened peoples and their ways of being, ranging from survival traditions such as hunting, to festivals and exquisite fine art:

The art has a characteristic combination of delicacy and strength that seems to reflect the whole society. It runs all the way from 17th-century engravings of fur-clad drivers merrily bowling across the snow in reindeer-drawn sleds to the terrific photographs of the Alaskan artist Brian Adams, large as life and presented on lightboxes.

This event, poignantly described by its curators as being ‘about the future’ was engrossing, humbling and mesmerising; in the eerily empty carriage of a London train, I was to bring home a more concrete awareness of our planet’s predicament, the frisson of a slowly disintegrating world - a world engraved with the brazen narrative of consumerism and our environmental impact, under the heightened pathos of the pandemic context. It was an experience that cried out to be shared: I would use it as starting point for a creative writing project. In search for examples of art as climate activism, I encountered artists whose work deserves celebration beyond their domain:

From recent iterations of the Venice Biennale, there was this heart-stopping sculpture by Lorenzo Quinn, conceived ‘to support this wonder of city that is threatened by climate change’ as Quinn explains on Instagram:

‘I hope my art brings a new focus of attention to a global calamity that we are faced with.’ “I have three children, and I’m thinking about their generation and what world we’re going to pass on to them. I’m worried, I’m very worried.”

Quinn’s work is the embodiment of the sheer communicative and political potential of art: in the case of ‘Support’, to rouse solidarity for the sinking foundations of a city which, having floated and even thrived on cultural, commercial and civic whirls for centuries, is now prey to the global warming tide.

I decided to structure my project around stimuli from these sources - the British Museum (including a stylistic evaluation of Cumming’s review), and Lorenzo Quinn’s work, which students could research further. I would encourage them to make connections with their own values and experiences; to identify their personal vision for the climate emergency and, through creative expression, add their voice to the conversation. I linked the project to the English Language syllabus and to their knowledge of ancient mythology (which features in much environmental art and its messaging about our origin and responsibility); and I hoped to facilitate the same awe, wonder and sobering sense of urgency that I felt.

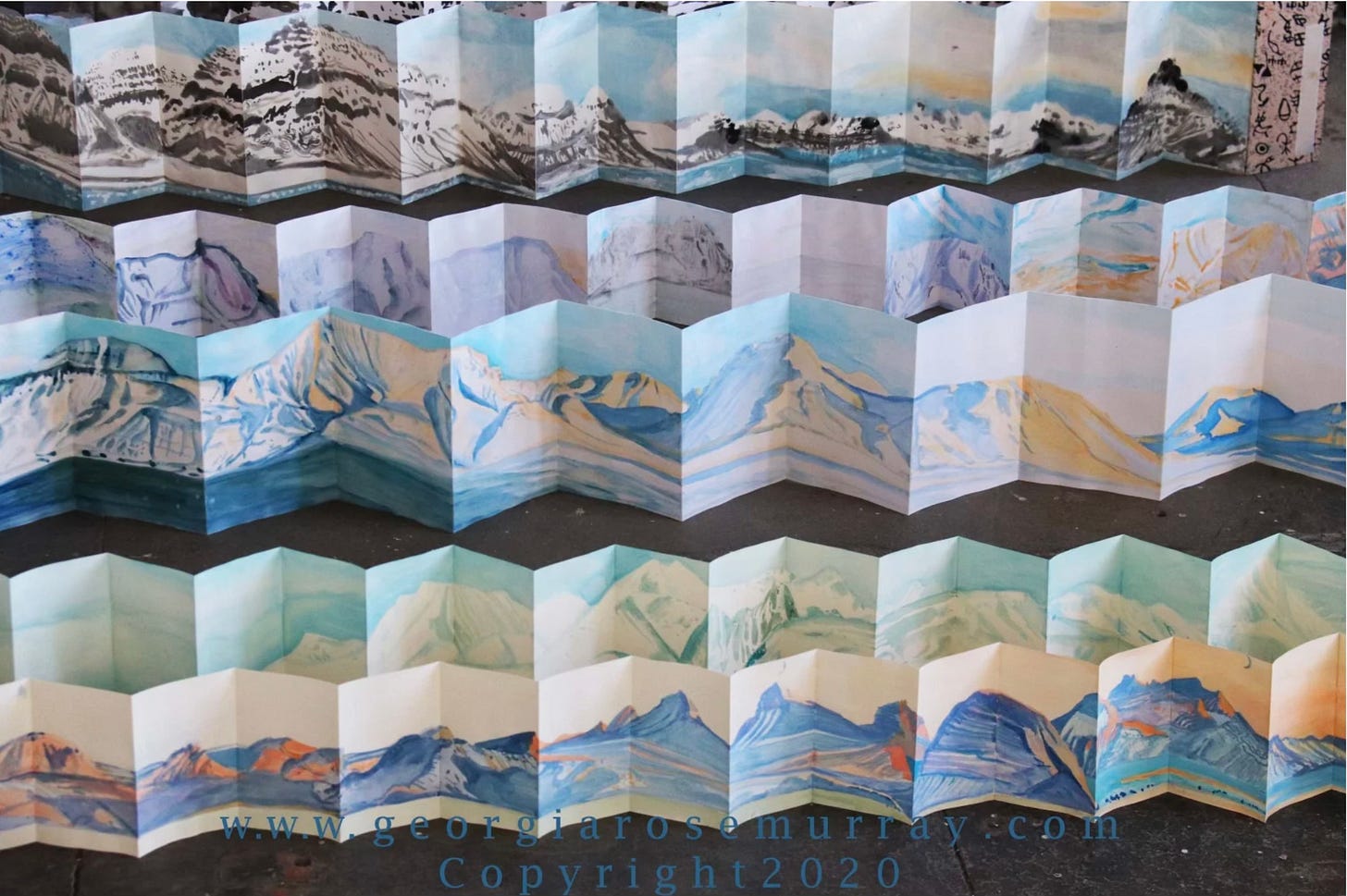

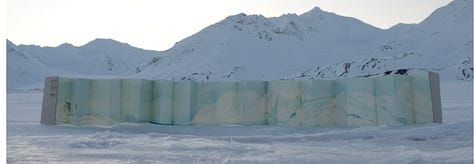

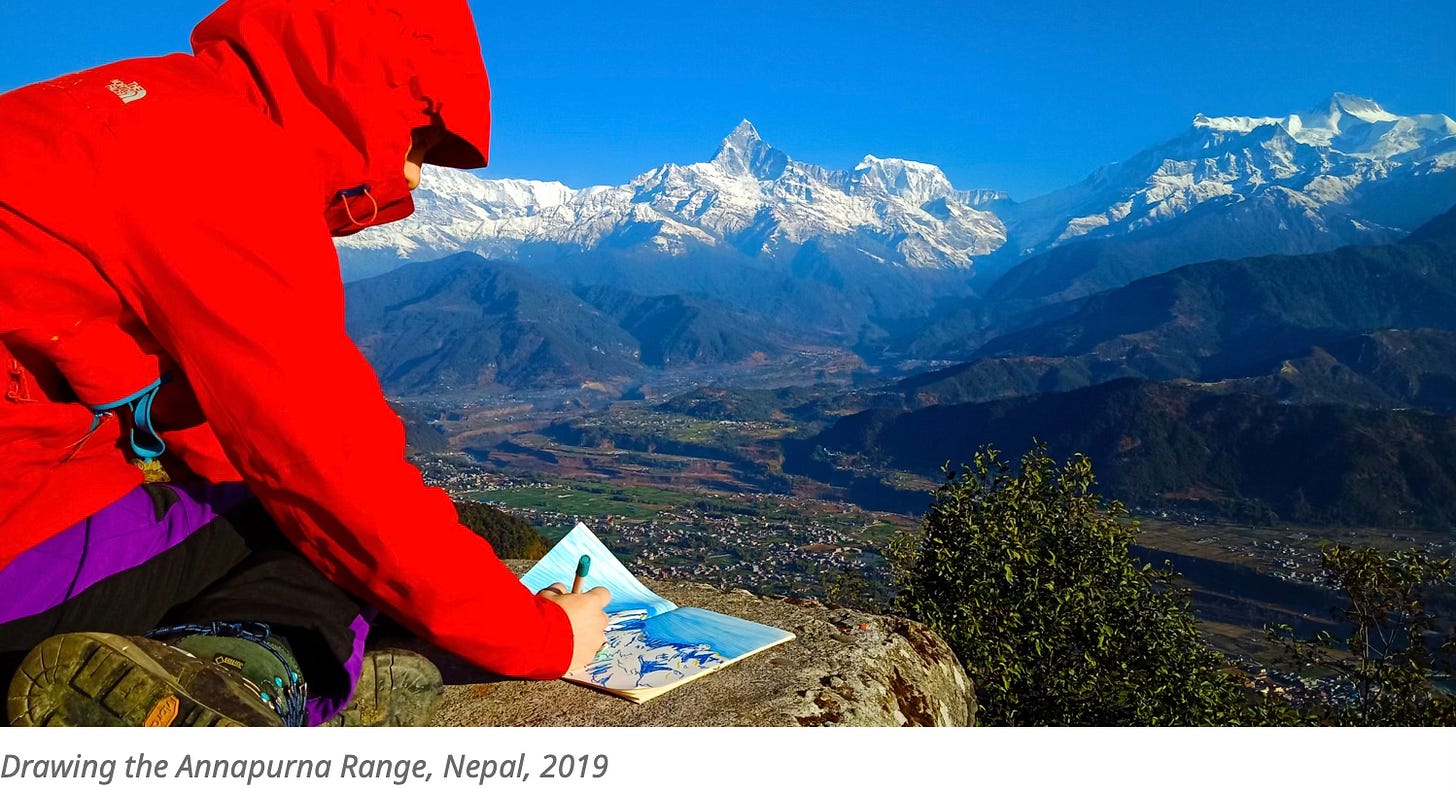

With the pandemic threatening to rage some more, there was no opportunity to take my students to the British Museum. But some joined me for a serendipitously timed talk by artist and explorer Georgia Rose Murray, hosted by our Art Department: Murray lives her work before committing paint to paper: her ethereal landscapes, capturing rare Arctic solar events, are initially worked into expanding concertina notebooks which belie the practical savoir-faire, physical resilience and commitment required to conjure them into being at temperatures as low as -40’C. Back in her Scottish studio, she works on big pieces of wooden board (heavy surfaces which wouldn’t be possible to carry in the Arctic landscape). She uses oil and gloss paint - unsuitable in the Arctic because of their high toxicity - to respond to all of the sketchbook drawing and painting completed ‘en plein air’.

On 1 March this year, Murray’s friend from The British Antarctic Survey - Iain Rudkin took her concertina paintings back up to Ny-Ålesund with him and photographed them in the landscape which inspired them (exactly five years after they were painted in situ). Murray recalls her previous stint there, which had been the subject of her talk:

On the 28th of February 2020, the sun rose over the mountain tops for 3 minutes, before setting again for almost 24 hours. I was incredibly lucky to be making a painting at that exact moment […] The sun wasn’t forecast to rise in Ny-Ålesund for another couple of days, so experiencing the golden sunbeams on that day was a beautiful and unexpected surprise.

Georgia Rose Murray used her research time to explore ‘the magical landscape and comprehend the delicate atmospheric changes the environment undergoes as the Arctic transitions from Polar Night to Midnight Sun’. She ‘mixed 96% Ethanol with pigments and paint instead of water to prevent the mediums freezing so quickly - despite this time-aid, icicles would freeze almost instantly on paper, brushes and on [her] skin.’ (PAINTING 2025)

We were spellbound by her tales of solitary work waiting for the once in 6 months sunrise event, of working with freezing paintbrushes - the ‘deep pull to fully connect’ and to translate ‘Arctic reality with colours and brushes.’

Murray’s sketchbooks stretch open to capture and follow the horizon:

See this gallery of her work for more detail about her expeditions and of her search to ‘gauge the magnitude of human existence within the universe’ through conscious and subconscious symbiosis with the extreme Arctic environment.

Some of the best written outcomes of my project were by the students who attended Murray’s talk. The characters in these stories, their personality and language, were born straight out of the adventures she had recounted. In particular, for a dyslexic pupil, this marked a turning point in engagement and long-term performance in English - the most joyous reward a teacher can hope for.

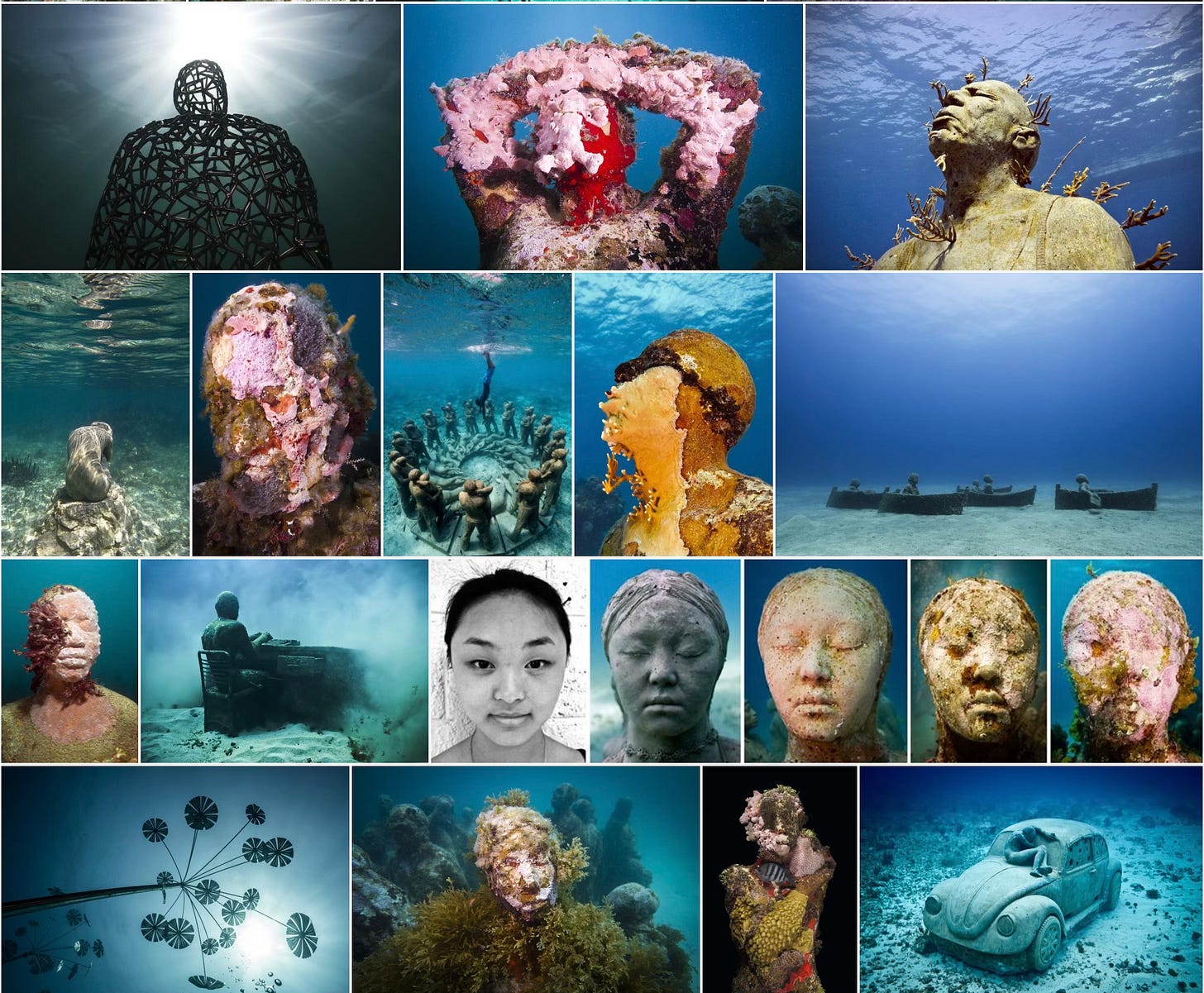

As final stimulus, I wanted an example of creativity directly targeting climate activism: I found just that in the complexity and depth of the latter-day wonder that are the underwater sculpture museums of Jason deCaires Taylor:

I learnt that for two decades Taylor, award-winning sculptor, environmentalist and underwater photographer, has been creating and submerging underwater museums and sculpture parks of dramatic scope, scale, aesthetic and emotive load. To date, he has submerged ‘over 1,200 living artworks throughout the world’s oceans and seas’: you can visit these sites from the dry comfort of your home: Mexico, Grenada, UK, Bahamas, Maldives, Spain, Indonesia, Norway, France, Cyprus, Australia. I urge you to watch Taylor’s TED talk and browse his moving image galleries: they will change the way you think of the relationship between art, context and responsibility.

'As soon as we sink them, they belong to the sea.’

The themes of Taylor’s monumental installations relate to a range of contemporary issues and to how each leads back to climate emergency. Here is the link to the full, spectacular gallery , where you can read about the scientific, ethical and social impact of Taylor’s work, and the fascinating practical and cultural aspects of his colossal creativity process.

In the video gallery of individual projects you can witness the role of underwater light and movement in the artistic, scientific and environmental messaging of each piece. You can enjoy liquid chiaroscuro, nuances of underwater light and shadow, of myriad marine life - nature engaging in creative dialogue with the man-made. You will see the wonder of the biological events that these submerged sculpture parks become; you will understand Taylor’s call for recognition of the sanctity of oceans as more than infinitely awe-inspiring expanses of luminous blue.

Highlights from Taylor’s monumental catalogue:

The Silent Evolution – one of Taylor’s most iconic works; hundreds of life-size figures (casts of local community). Isla Mujeres, Mexico

Vicissitudes – circle of children holding hands, symbolising unity and the passage of time; The Lost Correspondent - figure of journalist at typewriter desk - commentary on media and communication in the modern world. Both at Molinere Underwater Sculpture Park, Grenada

Man on Fire – evocative human figure engulfed in flames - humanity’s destructive relationship with nature. Lanzarote, Spain

Ocean Atlas – 28ft tall, 60 tons heavy sculpture depicting young girl carrying the weight of the ocean on her shoulders, symbolising the environmental responsibility placed on younger generations. Bahamas

Beside the awe-inspiring scale, thematic and political symbolism, and aesthetic appeal of his work, Taylor’s most remarkable achievement is his direct harnessing of the regenerative power of the ocean: each sculpture, of pH-neutral material, structurally attracts and hosts life, in every way reversing the toxic tide. In doing so - and just by existing - the sculptures also attract human attention away from reefs and other fragile environments, by enticing snorkelers, divers and photographers in their direction instead.

Thriving in aesthetically fascinating organic layers off the surface of man-made art, newly-formed marine colonies embody the answer to the perennial nature vs nurture debate. But also the emergency of destructive human impact side by side with our capacity to create, heal, regenerate. Moreover, by exposing our own transience, they become a kind of sculpture in reverse: we, who are destroying marine life, are being sacrificed to it. As coral and fish - including endangered and rare species such as the Elkhorn coral, declared functionally extinct - emerge to populate Taylor’s sculpture parks, we are reminded that our relationship with nature, the marine environment specifically (on which our existence depends), is one of mutual consequences.

Far from leaving the Romanticism and aesthetics of art behind,

The subsequent natural changes are intended to explore the aesthetics of decay, rebirth and metamorphosis. [His] projects are not only examples of successful marine conservation, but works of art that seek to encourage environmental awareness and lead us to appreciate the breathtaking natural beauty of the underwater world. (from Taylor’s website).

I personally find them strikingly beautiful in themselves, including for the stories they tell.

Finally, if the Romantic Sublime is the aesthetic and emotive response of awe and terror in the face of natural phenomena immensely more beautiful and powerful than anything we can conceive; if it is the definition of a space for contemplation and critical engagement with the human condition, of our place in a larger universe, alongside - rather than above - the natural world, then the work of artists celebrated here surely also represent the Sublime:

the Sublime as human resilience

the Sublime as creative drive

the Sublime as impact - impact for change

As our natural ecosystems face ever greater challenges these creative approaches to raise awareness are critical to help inspire people to implement the changes need to support the health of our planet. (from Taylor’s website).

Art can have an immensely powerful voice: it reaches minds and souls across language, cultural, temporal or spatial boundaries. Here I only dwell on a subjective selection of climate activism through creativity but, as argued in my first post in this ‘Art and Intent’ series, all art is inevitably political, a product of its times, even when reacting against them:

Cultural and anthropological exhibitions facilitate concrete understanding of significant contemporary issues. In this case, of the Arctic as more than awe-inspiring polar icecap, but rather as threatened home to over 40 ethnic groups, endangered ways of life, endangered flora and fauna. By awakening interest, awe and respect, the British Museum exhibition also revealed our impact on the survival and creative expression of peoples whose way of life continues focused on sustainability, unlike in our consumerist society.

The work of artists like Georgia Rose Murray, Lorenzo Quinn, Jason deCaires Taylor, hold us spellbound with their creative and ethical vision, their aesthetic weight and delight. In the case of Murray, the additionally dimension of adventure and resilience, at the core of her creative endeavour and in her courageous choice to work in extreme conditions. She herself describes her paintings as ‘initiated by sublime experiences’ and essential in encouraging ‘heightened states of awareness’.

Meanwhile, Taylor’s underwater museums and sculpture parks, even while ostensibly resisting an aesthetic drive, are the 21st century riposte to the Romantic Sublime - of scale and magnificence unsurpassable by any other form of creative expression.

While the Romantics contemplated the boundlessness, awe-inspiring qualities of the environment, here we are at the stage when, having abused it, we owe it everything in our power to help regenerate it. But also, in Taylor’s words, to recognise its sanctity.

Next time I run my creative project, I will take my students to Shelley’s iconic sonnet about the legendary king’s arrogant illusion of power before mightier Nature:

Ozymandias I met a traveller from an antique land, Who said—“Two vast and trunkless legs of stone Stand in the desert. . . . Near them, on the sand, Half sunk a shattered visage lies, whose frown, And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, Tell that its sculptor well those passions read Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed; And on the pedestal, these words appear: My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair! Nothing beside remains. Round the decay Of that colossal Wreck, boundless and bare The lone and level sands stretch far away.” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792-1822)

And I will ask my students to evoke, in the mode closest to their heart, the devastation they would not want future travellers to find in our antique land.

‘Empower the youth so they can help rectify the endless mistakes we have made.’ Jason de Caires Taylor

Additional recommendations:

Yann Tiersen will play at the Barbican Centre, London, on 19 April

copies of Georgia Rose Murray’s notebooks available from 'Unseen Notebooks'

stunning pictures of life and work in Ny-Ålesund (most northern research station)

full documentary about Jason deCaires Taylor ‘the artist who redefined the relationship between art and nature’:

Lovely to read this again. Meanwhile, Torres Straight Islanders recently took the Australian Federal Government to court, claiming they were owed a duty of care with respect to climate change by the Australian government. The judge was sympathetic, but the court case was lost.

Ha! I just yesterday learned about Jason deCaires Taylor, while doing research on artificial reefs, and now here he is again. I love the way the natural world so quickly reclaims man-made stuff. It should keep us humble. Ozymandias is perfect.