Echoes of Sappho

'I have been told that Sappho was a woman, and that Plato and Aristotle placed her with Homer and Archilocus among the greatest of their poets'. (Virginia Woolf)

For two weeks this post has been waiting for an opening. Many possible introductions passed by:

something about creativity - imitation vs originality; the value and purpose of each; cultural or historical variations in attitudes towards them

inspiration: what drives us to respond to someone else’s creative output? Why are we easily open to influence?

something more specific, e.g. about imitatio, the Renaissance art of imitation and idealisation as response to the arts of classical antiquity; perhaps also its equivalent in other cultures and traditions

poetry vs visual representation: which mode gets closer to the authenticity of human experience? Does it even matter? Interesting read here proposing that visual arts impact our ‘older, more reactive brain system’, while words, often ‘nuanced and ambiguous, might require more thought’ before affecting us. Evidence certainly suggests that in the trajectory of evolution visual pre-dates verbal literacy.

the idea of dialogue between modes of expression, such as ekphrasis (responding to a work of art through another form, e.g. ‘translating’ a painting into a poem) and reverse-ekphrasis (responding to a poem with a painting).

My introduction could also easily have been something straightforward, like a biographical synopsis of Sappho’s life and legacy. However, as her life has already been subject to millenia’s worth of speculation, the focus here is on aspects of her legacy as a way into how and why we might participate in the art of ‘another’; the joyful experience this can be (regardless of one’s competencies).

In this acclaimed Virago Press volume (check this pithy review ), Anne Carson collects the surviving papyrus remnants of Sappho’s nine books of lyric verse (‘lyric’ because originally composed to be sung to the lyre).

‘Sappho was a musician’, Carson’s introduction announces, momentarily unsettling any orthodox image of Sappho as most prominent female poet of the antiquity. The subsequent revelation that none of Sappho’s music survives acts as melancholy prelude to the confirmation that indeed ‘Sappho was also a poet’.

It is as poet that we have thought of Sappho for over 2000 years, even though only one (or possibly, at most three) of her poems reach us in their entirety. Carson tells us that the numerous ‘whole’ poems in her complete anthology If Not, Winter are in fact citations of Sappho by (male) authors of the antiquity.

Sappho’s birth is estimated around 630 B.C. In Who was Sappho and why do we care?, Adwoa Owusu-Barnieh offers a perceptive evaluation of the ‘Sapphic persona’ across the 2648 years that divide us:

‘Was there ever even a Sappho? We simply do not and cannot know for sure. [She] has become a cultural icon … not an individual identity, but rather, a symbol …– not a person, a poetess, a lover […] The fragmentary poetry attributed to the name is emblematic of our cultural progress towards self-expression, individuality, humankind’s inherent multiplicity, sexuality, development, loveless-ness, longing and memory.’

[…]

When we speak of Sappho we reiterate the human desire for temporal markers of shifts in the collective consciousness. To speak of Sappho is to define when we believe the advent of the poetic ‘I’ began. A stylistic poetic feature that we, as contemporary consumers of literary culture, frequently take for granted […]: the expression of one’s private world.

Owusu-Barnieh highlights the eurocentric, even anachronistic lens afforded us by unabashed cultural and historical revisionism. She also pinpoints well-known literary works influenced by (the idea of) Sappho across time: Ovid’s Heroides, Baudelaire’s Flowers of Evil, Sarah Waters' Tipping the Velvet. To her list, I add my absolute favourite, the audaciously vivid prose, of timbre at once post-modern and threaded with Sappho’s discourse, of the Booker-shortlisted After Sappho (which also inspired my short piece From Handpress to Substack). If someone other than Anne Carson has so far attained the accomplished feat of truly ‘echoing’ Sappho and her legacy, then this has to be Selby Wynn Schwartz, whose fragmentary novel is a polyphonic ode to the female creatives of the Modernist movement.

Other than through her life choices, Sappho’s timeless cultural relevance is therefore deeply rooted in a vision and use of poetic voice that transcend boundaries of time and space. As Owusu-Barnieh observes, we should still ‘care’ about Sappho’s legacy because it offers an opportunity - in this increasingly complex, troubled and beautifully diverse world - to project our own experiences onto the iconic ideals of Sappho’s persona and poetry:

I too am swayed by the almost - yet never quite - mythical Sapphic persona; I celebrate her role as part of the cultural history I’ve inherited by reading her work and about her work, by discussing it, by painting the ‘echoes’ of it shared here.

Dwelling on Sappho’s creative output we contribute to exposing the largely Western, gendered paradigms that define the reception of creativity as historically male-dominated. I find particularly attractive the idea that Sappho’s ‘I’ might have been the first subjective voice in Western poetics, therefore worthy of the accolade of being the mother of lyrical verse.

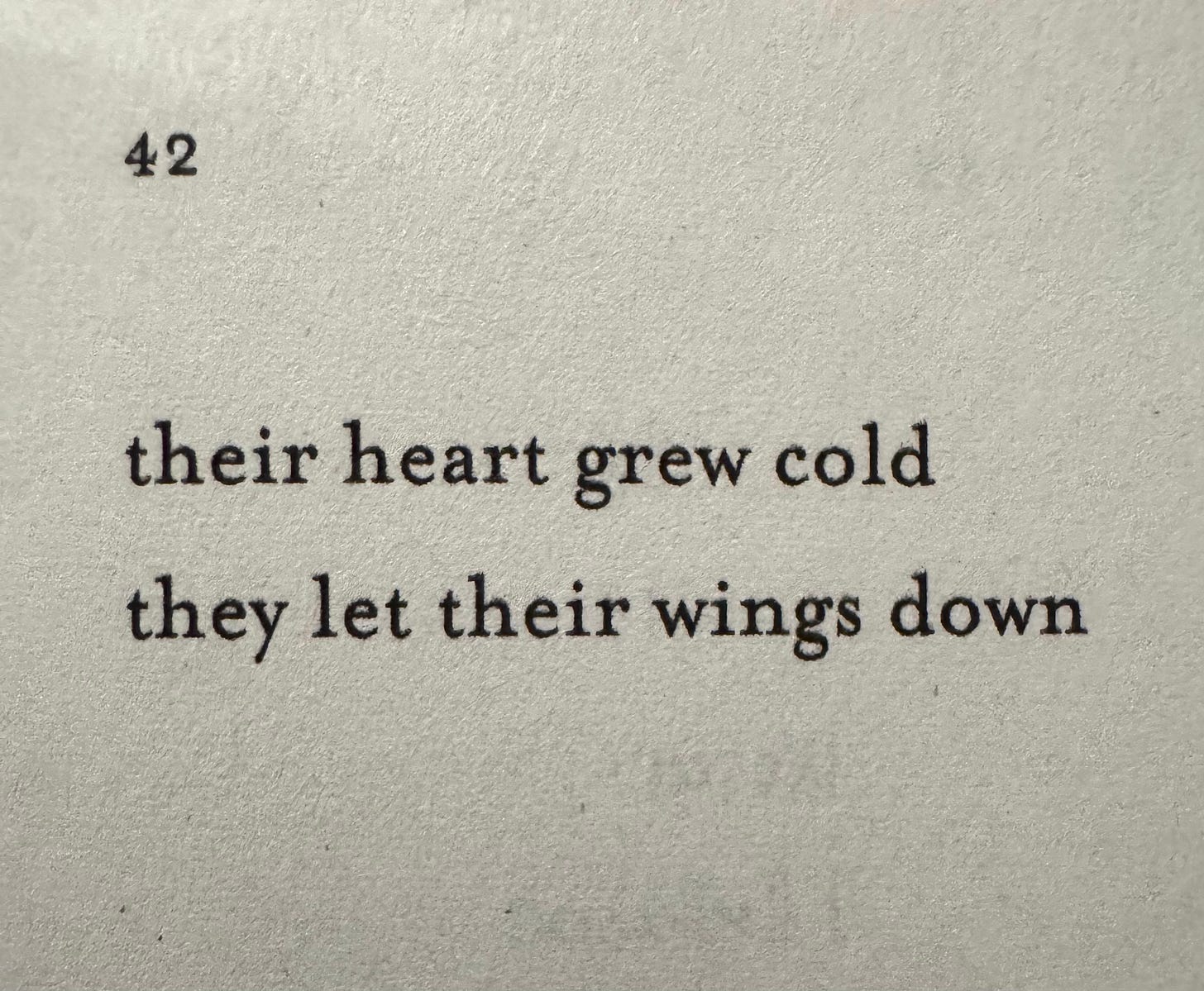

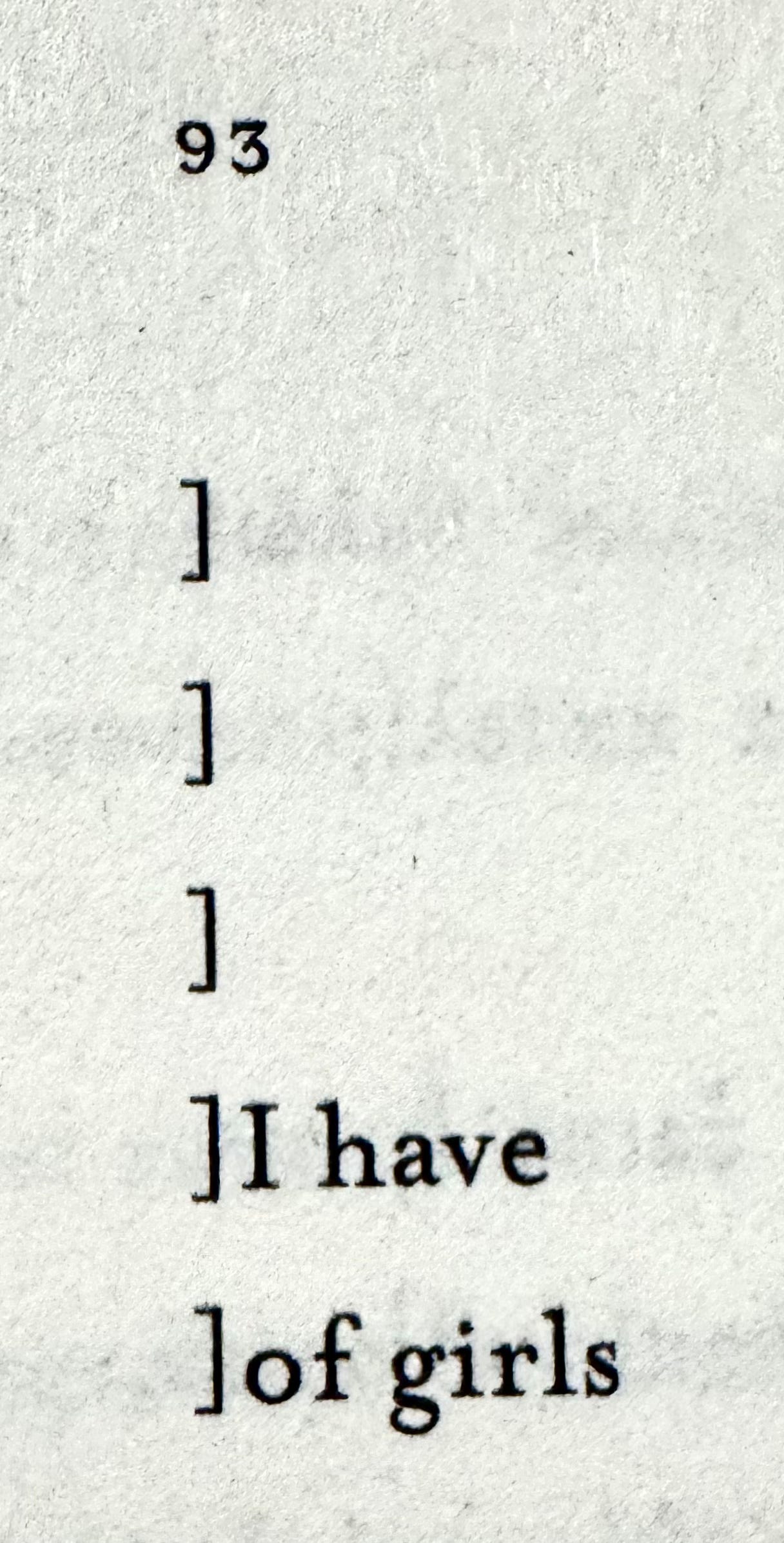

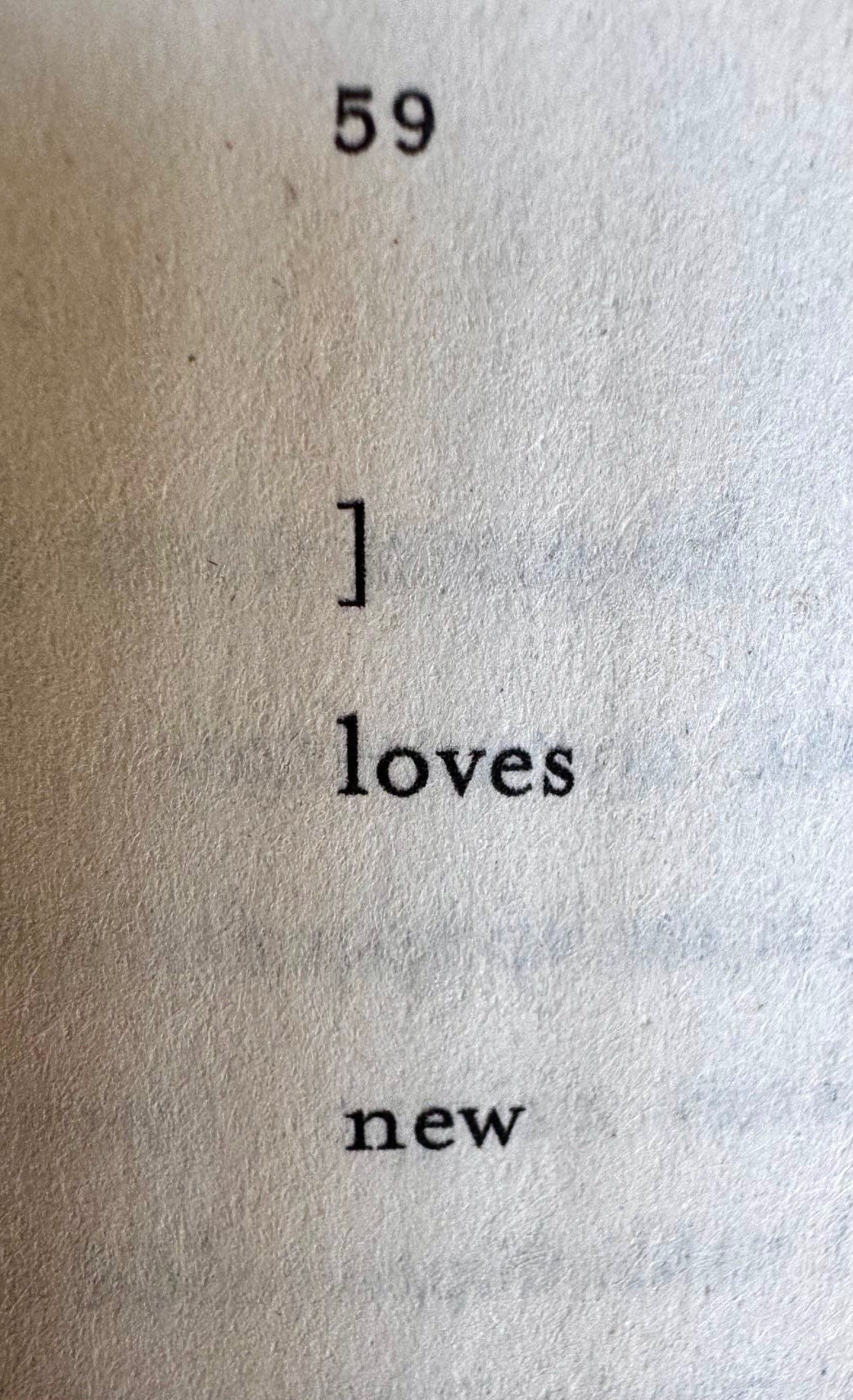

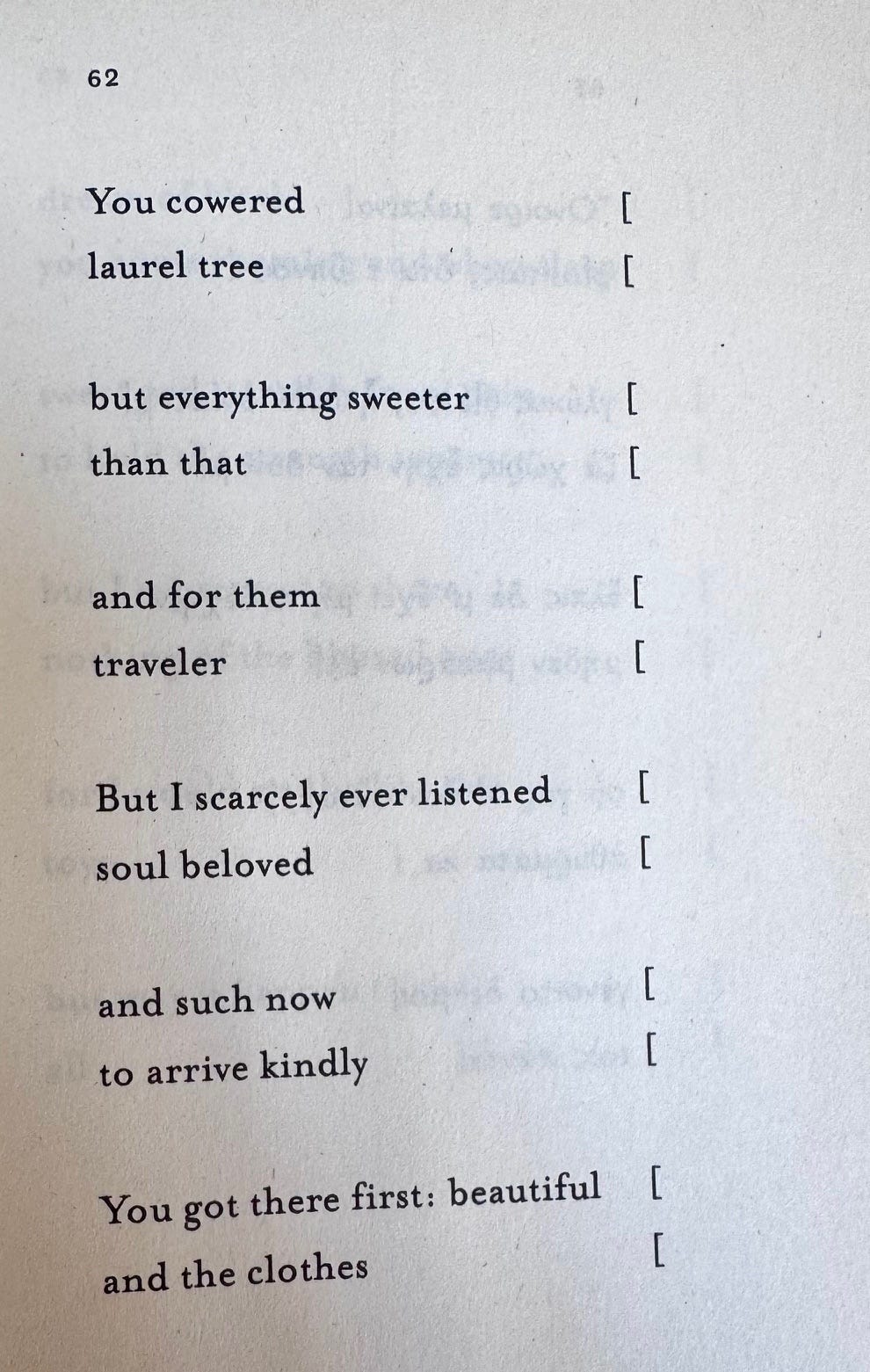

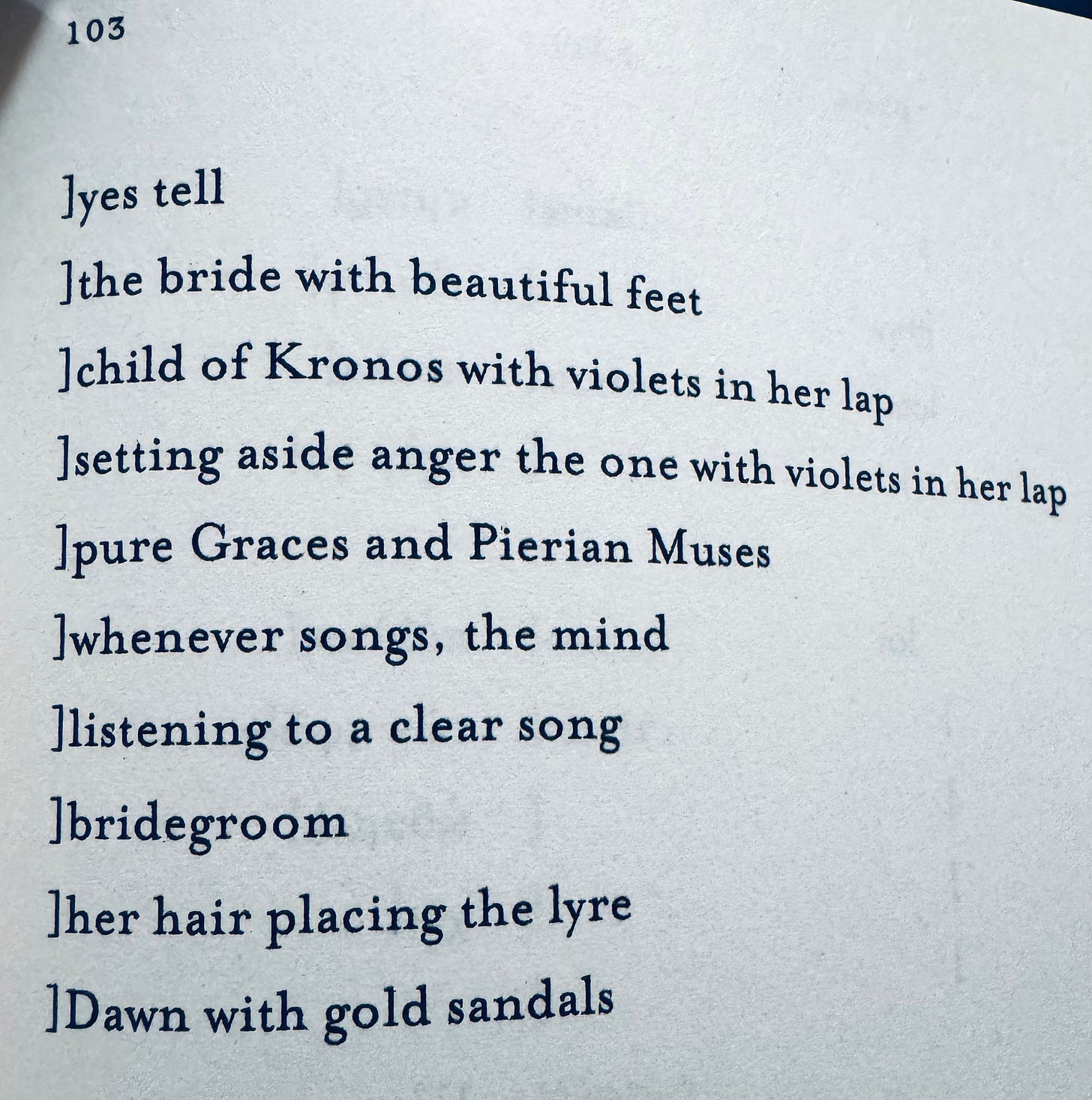

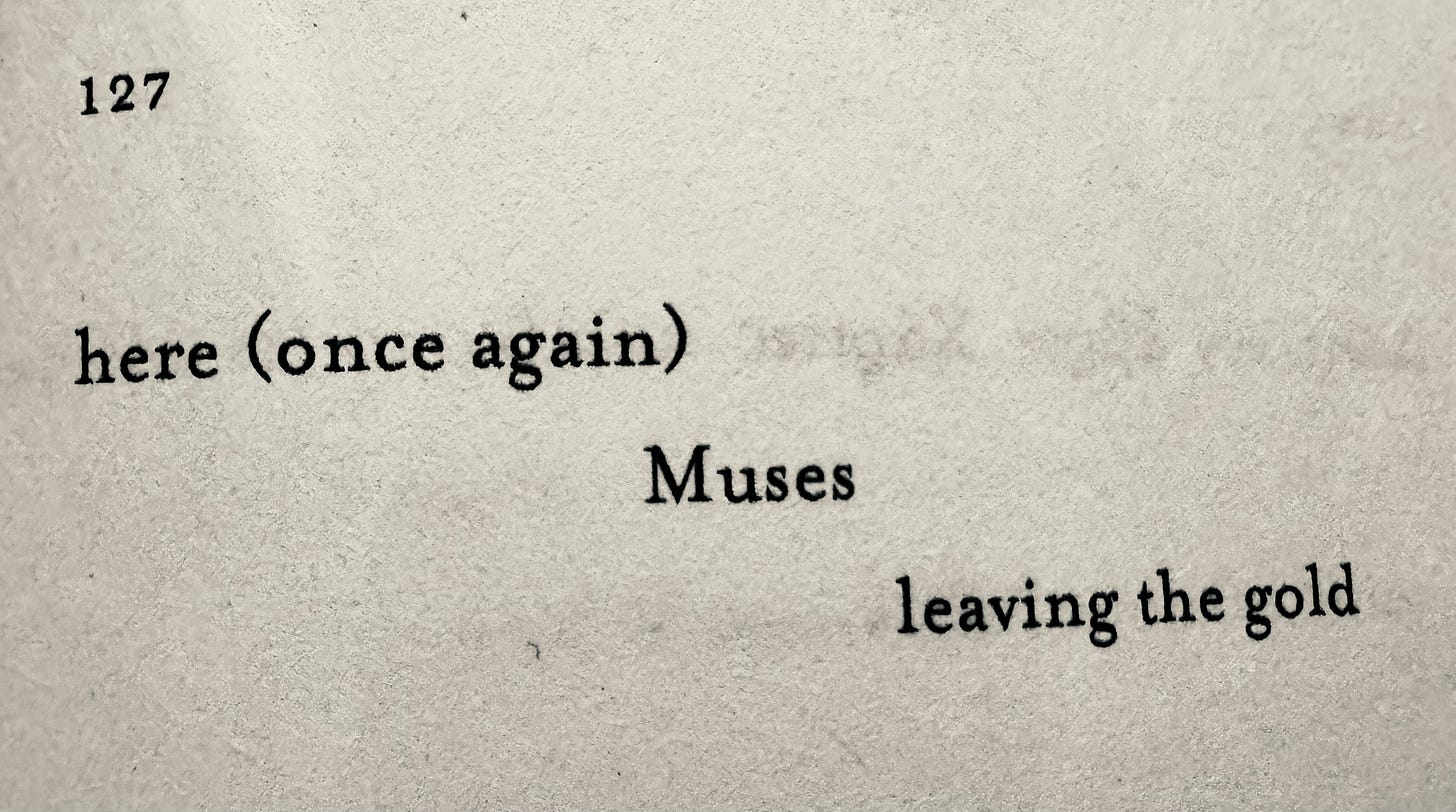

What particularly engages me in literal and artistic re-readings of Sappho’s poetry, is its fragmented nature, the brittle, alveolar, coral-like structure of its remains. The unfulfilled ‘parentheses’, the potential cradled in the arms of Carson’s square brackets [ ], used to represent not omissions from the original poems, but loss: papyrus and lexical crumbs, disintegrations, perforations.

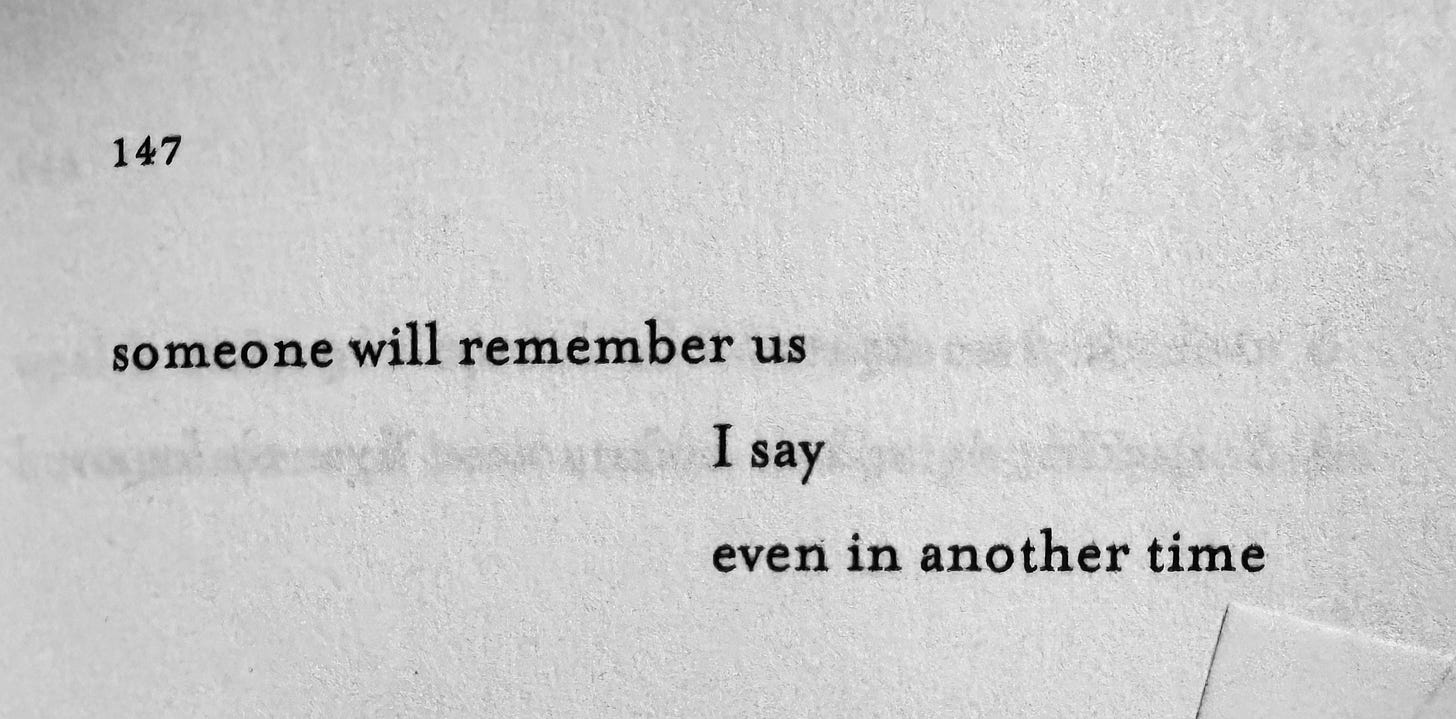

On the clinical candour of blank paper, Carson carefully lays, side by side in Greek and in English, 192 fragments of imperfectly preserved metrical feet of natural imagery and mythological allusions, assertive and dewy with longing, outstretched for our fingertips, our gaze. Held in square brackets, the emptied core of a line or verse becomes a visual signifier of [lost] potential. Something was there, organically contained, floating unfettered in the amniotic fluid of poetic syntax.

Through absence, the fragile materiality of these odd words and phrases pulverised by time only serves to highlight the power of collective memory - be it through the intangibility of oral tradition or the concrete preservation effort that is museum curation. Memory, in whatever mode, is what we owe our trail-blazing predecessors whose achievements illuminate our days - which, in Sappho’s case, is the path to re-calibrating voices and legacies written out of history.

Owusu-Barnieh observes that the incompleteness of Sappho’s poetry reflects a broader theme of absence in human experience, while for Carson the brackets are ‘an aesthetic gesture towards the papyrological event, rather than an accurate record of it’. To her, ‘They are exciting’, just as they are for me and hopefully, by the time you have finished reading this, also for you.

And yet, however skilful and culturally attuned Carson’s rendition in English might be, much more than friable phrases is lost to us: in the words of 20th century intellectual giant, Umberto Eco, translation can only ever be ‘almost the same thing’. Carson herself warns that translation should not be ‘a reason to miss the drama of trying to read a papyrus torn in half or riddled with holes, or smaller than a postage stamp’; that ‘brackets imply a free space of imaginal adventures’.

Thus, beyond Sappho’s surviving words, the sight of empty brackets offers us a concrete, fortuitous space to participate, however whimsically, in a creative act. In reading a poem, each of us contributes to its meaning in our own way. Interpretation relies on unique emotive and cognitive reactions defined by everything that makes us who we are, and by the context in which we are reading, including environmental factors. How we fill empty parentheses or how we respond to lines or imagery, including by ‘echoing’ in another mode of expression, will always be uniquely ours, a subconscious act most likely driven by a primeval need to connect. Often, our contribution will spring out of emotive response and by-pass reasoned thought. Regardless of the shape it takes, the heartbeat of interpretation is wonder.

Nested inside the human need to connect, our drive for semantic and syntactic coherence is essentially a yearning to ‘make sense’ of something we are presented with in an unusual form (e.g. through artistry). Momentarily extracted from the comfort zone of prosaic existence, we depend on the power of imagination to help us make sense, to respond. This is regardless of how long we pause to think or feel: the gap between the object we are looking at, and what it might mean, is filled by our participation (the act of ‘reading’) in the first place.

This is not only true of poetry reading: it happens also when we read a comic: we ‘fill’ the space (called ‘gutter’) that separates panels in a graphic novel by ‘imagining’ the meaningful transition between them. It also happens when we bridge the silence between acts in a play; when we subconsciously connect (assign meaning to) split-second scene changes in a film - also in the speedy transitions between shots, even frames within shots. And it happens when we contemplate apparently disconnected or multi-sensorial stimuli of abstract art. Arguably, any form of creative output depends on an audience for meaning (be this even an audience of one: the author).

We can see this through a closer look to some of Sappho’s poems. Fragment 59, for example, is full of possibilities, like a window open towards luminously expansive fields:

Meanwhile, Fragment 62 throws the gauntlet of creative licence across the table:

69 is simply provocative - when has a set of 3 square brackets ever held so much potential, or carried a more serendipitously witty title?

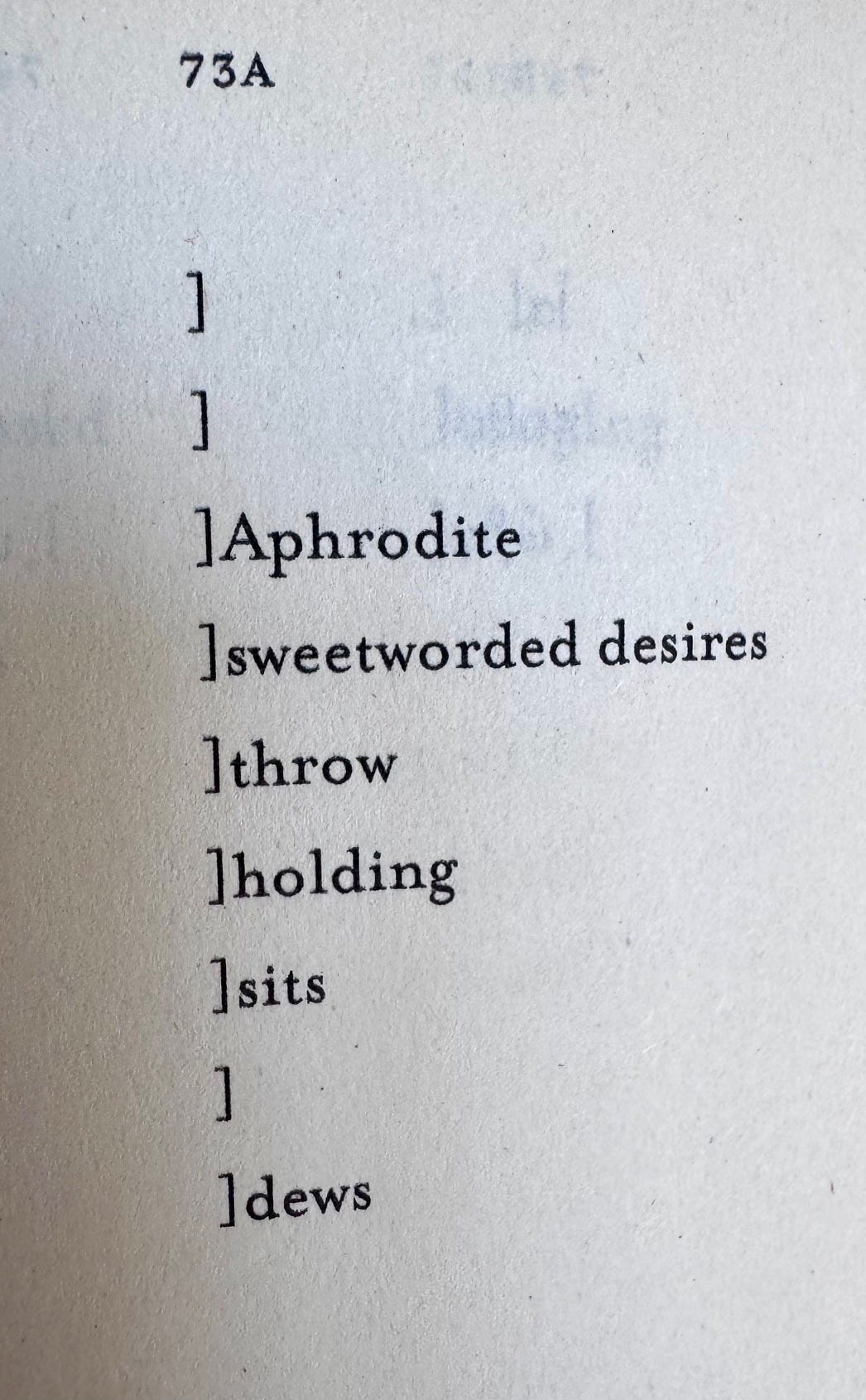

The heart of 73A offers up the Goddess of Love herself, sumptuously rising out of a swirl of ‘sweetworded desires’. Aphrodite’s trappings are left to our imagination:

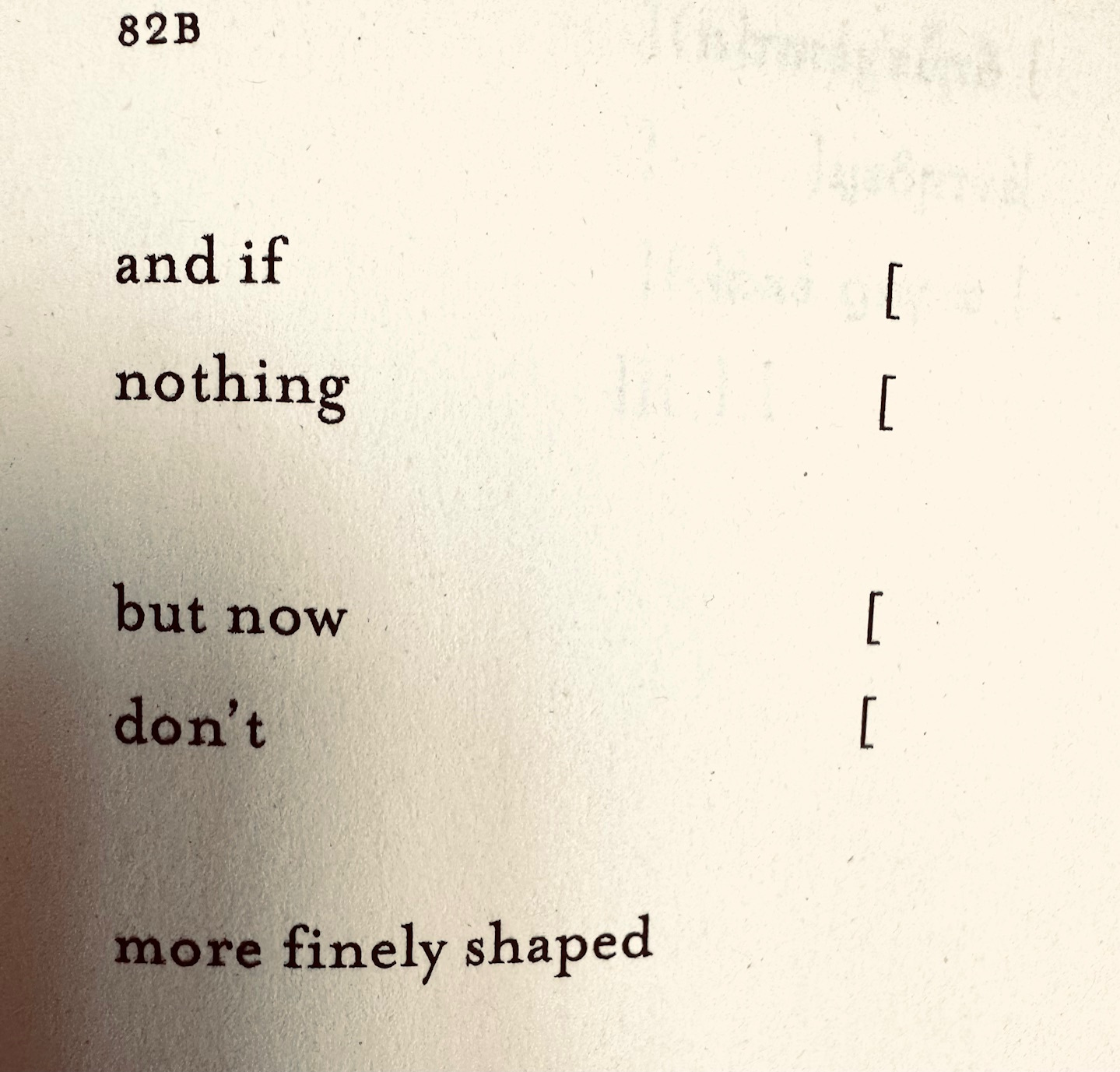

And 82B would make a perfect warm-up exercise for creative writing class:

If your stylus needs a helping hand:

How might you fill some of the gaps in these fragments, with individual words or full phrases? Nouns or adjectives?

Do you sometimes, instinctively, fill in the blanks with an emotive response?

How does your version of what could be change the poem from how you initially read it?

What does your contribution reveal about you, ‘here’ and 'now'?

Would you have filled in the blanks differently on 14 February 2022? On Christmas Day ten years ago?

…Or somewhere else, or when not alone, or not with other people… In a school? At a party? In a late evening writing group?

What if working with a painter? A composer?

Where were you tempted to be rude?

You could play this as brain (and heart) teaser to pose more significant questions, such as: What can parenthetical contributions reveal about ourselves, as audience, as society? After all, these shattered poems were composed to fit the flow of original lyre tunes, rather than being deconstructed in February 2025, to a Substack audience...

We can think of participation, through echoes, imitation or gap-filling, as collaborative with the author and with the cultural current which has brought her to us. If you are a woman reader or painter or musician, you might for a moment even feel part of a creative sisterhood.

Whoever we are, in reading and responding, silently or loudly, we contribute to human endeavour, to propagating a creative act, however humble or ephemeral.

And so the fractured survival of Sappho’s poetry can bring us closer to grasping the elusive nature of the creative spark smouldering inside every single one of us. In a more general sense, it is the fate and privilege of the artist / audience relationship to be bound by dialogue and echo across cultural and temporal boundaries: from private contemplation to political reflection, from inter-textuality to whimsical ekphrasis.

Carson concludes her introduction to If Not, Winter with a nod to Walter Benjamin’s declaration about the translator’s task, in that she is ‘not quite sure how to hear Sappho’s echo’, not beyond a ‘tingle’, ‘now and then’.

Carson may not always hear it, but we certainly feel it, turning the pages of her book from one fragment to the next. Sappho’s legacy lives on.

See also:

I look forward to following your work. I think the 'work in progress' pieces already encourage a gap-filling exercise. And then it gets really exciting when one reads the description of your process, how the gaps were eventually filled, and why. The fact that you recounted the process verbally added another opportunity for the audience to engage in meaning-making.

My favourite line of the day: "the amniotic fluid of poetic syntax." ❤️❤️❤️