Art and Intent

part one of an anthology of personal encounters and what I've learnt from them

Part One: ‘Art Does Not Exist in a Vacuum’

In the summer of 1990 I landed onto the shores of my new life in a foreign country with nothing but a small suitcase, my pocket-sized command of English, and a zest for learning which can only possess someone presented with the freedom of choice (any choice) for the first time.

I will always remember the simple, black on white ‘A Level Choices for 6th Form’ booklet handed to me by Someone Very Important at the school which had offered my bursary: I could pick anything I wanted? Really, anything? And I don’t have to study 16 subjects?

Encouraged to opt for just three A Levels to ‘immerse myself in’, I momentarily wondered how such an ostensibly limiting education system could work. But, giddy with possibility, I didn’t succumb to doubt; stroke of loss or luck, ‘options’ was a honeyed word. In the end I ticked four:

History and Appreciation of Art - because I grew up surrounded by my grandfather’s paintings and his small but mighty history of art library (you know those post-war books with manually glued-in colour plate illustrations on glossy paper?); and because I had no Art GCSE (a requirement for Art A Level).

English Literature - as homage to an extraordinary woman, my first English teacher; and to cultivate proficiency in the culture and language of my host country

Mathematics - being a universal language, and because I was good at algebra

Classical Civilisation - because my Ancient History teacher back home had for four years gripped our class of 40+ otherwise restless and hungry teens with the inexhaustibility of his infectious subject knowledge; and because I had largely forgotten my middle-school Latin and never touched Greek, so couldn’t opt for straight Classics.

But pursuing four A Levels was a rare thing, even before the A Level reform. Another Important Person advised me to drop one subject at the end of my first 6th Form year, to concentrate on the three that will prepare me best for university entrance (albeit with further embarrassment of choices). In the end I dropped Classical Civilisation: it was the subject I could most easily continue independently - and the boy behind me regularly got away with squirting ink on my white school shirt…

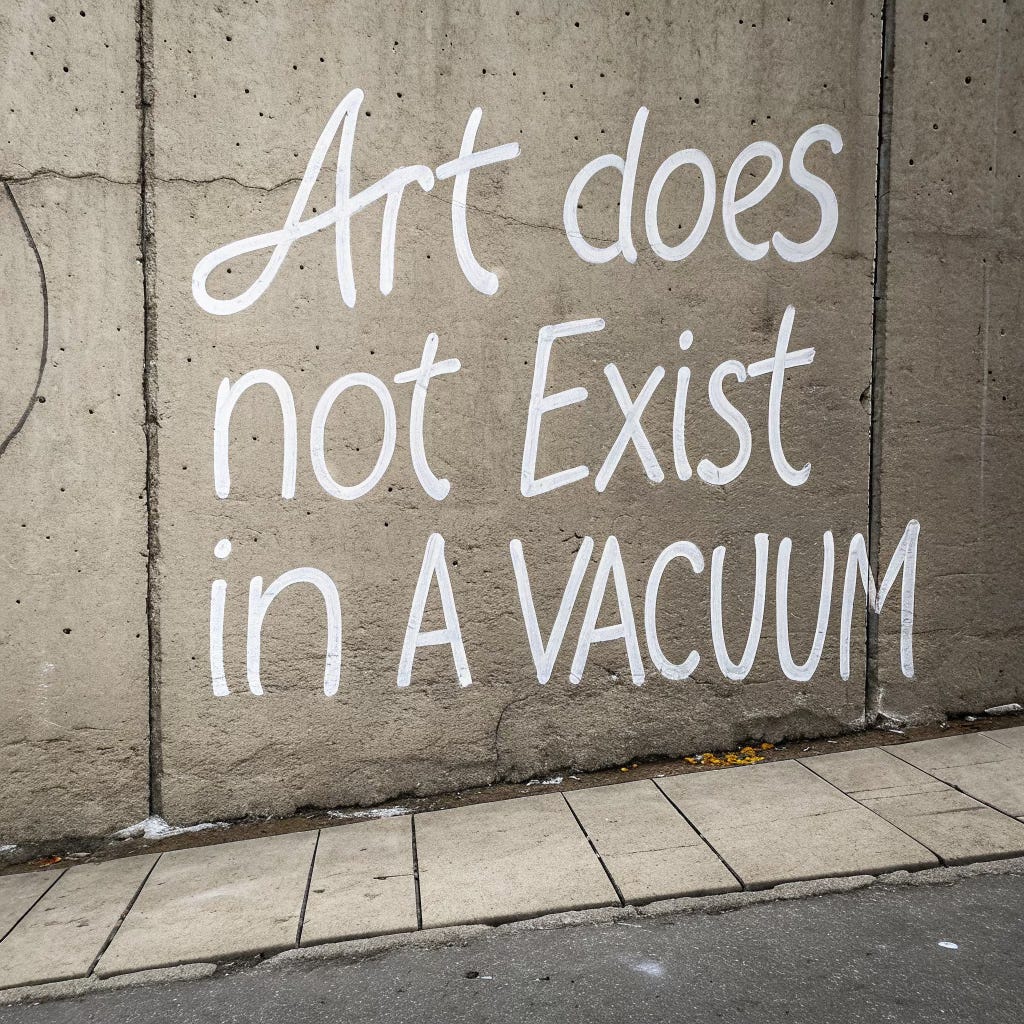

The lesson I was most excited about - the very idea of it as school subject was ungraspable, akin to brushing past celebrity shoulders - was History and Appreciation of Art. Indeed, the take-away from our first lesson stays with me to this day, be it due to the vivid literal picture (of a vacuum cleaner!) conjured by my rudimentary English, or because I was hooked on the timbre of Miss Johnstone’s voice as she paced with deliberate calm towards the heavy mahogany table where our class of six sat poised and ready to take notes.

With resounding clarity, Miss Johnstone announced:

Today, working with students of any age, inclination or ability, I often bring them back to this core idea: that art does not, cannot exist in a vacuum; that it has always been and always will be a product of its times, for its times.

In discussions of ‘art’ I mean all modes of creative expression. I’m neither an Art nor an Art History teacher, I work with literature and with language. If I were to guide my students through these outside of the ‘wider’ picture, much of what enriches our culture, the stories we read and the stories we tell, would remain obscure to them.The words on the page invariably belong with other words on other pages. They also belong with other modes of creative expression, currents of thought, historical tides.

An artist never works under ideal conditions. If they existed, his1 work wouldn’t exist, for the artist doesn’t live in a vacuum. Some sort of pressure must exist. The artist exists because the world is not perfect. Art would be useless if the world were perfect, as man wouldn’t look for harmony but would simply live in it.

History of Art has long fallen casualty to subjects that apparently lead to more ‘real’ professions - in 2017, only 16 state schools and 90 fee-paying schools in the UK still offered the subject. This problematic reduction in creative subjects and the impact of this on the younger generations remains a subject of debate and scrutiny in the UK.

Just as Miss Johnstone must have done with our small class, I often engage my students in discussions about the meaning and impact of creative endeavour as intrinsically rich and malleable, fluidly subject to new readings and interpretations specific to an audience, in its own time and place. I tell them this is its super-power.

So how can there ever be room for art that is exclusively for art’s sake, regardless of the mode in question, when:

… we immerse ourselves in a hobby that holds us actively, creatively, spell-bound ‘in the moment’

… at the end of a day’s work, we lend our voice to a choir or a dance ensemble

… creative output becomes successful enough to provide material as much as spiritual sustenance

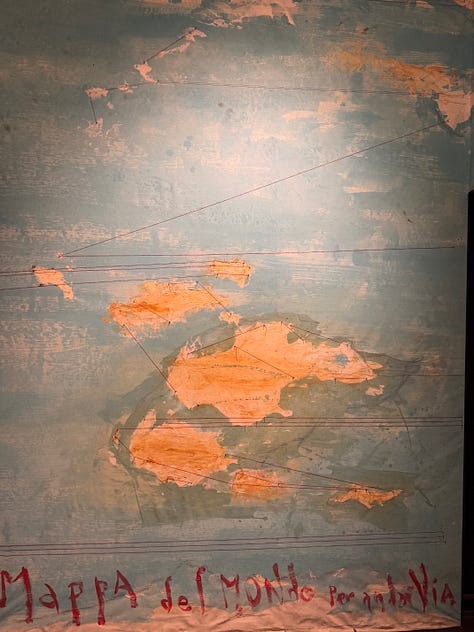

Regardless of output, be it serious or whimsical, creative expression will always be defined by our own, personal, time and place, cradled in the wider context which - for better or for worse - nurtures us.

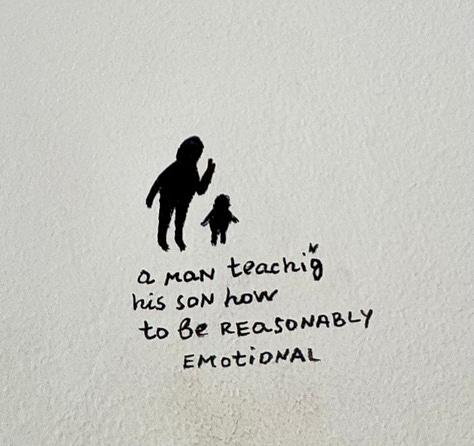

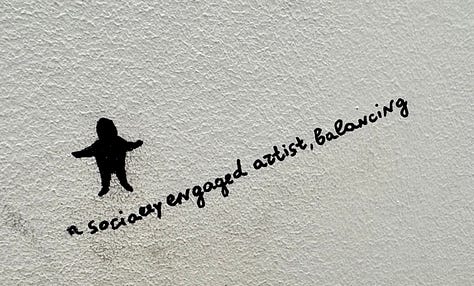

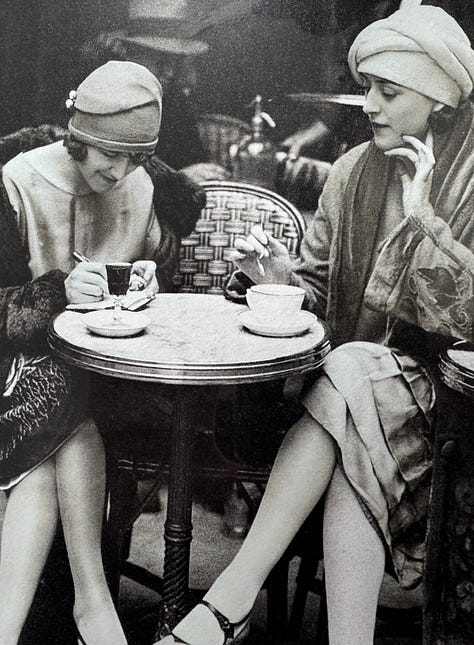

Selection of tongue-and-cheek thumbnail graffiti scattered all over the stairs and walls going up to the Emotions Retold by Contemporary Art exhibition, Chiostro del Bramante, Rome (December, 2024). There’s an additional layer of self-reflexive irony in the fact that this graffiti is in fact part of the exhibition experience.

Once we expose a creative contribution - if only by slightly lifting the veil of self-doubt - to an audience of any kind, and they catch glimpse of it, it [also] becomes theirs. Often (think of fashion, pop music or art postcards ‘in [this] age of mechanical reproduction’2), a creative contribution somehow belongs more obviously to its audience than author. The meaning an audience will assign to it - itself a product of their own personal time and place - will most often refract and reach far wider than originally intended.

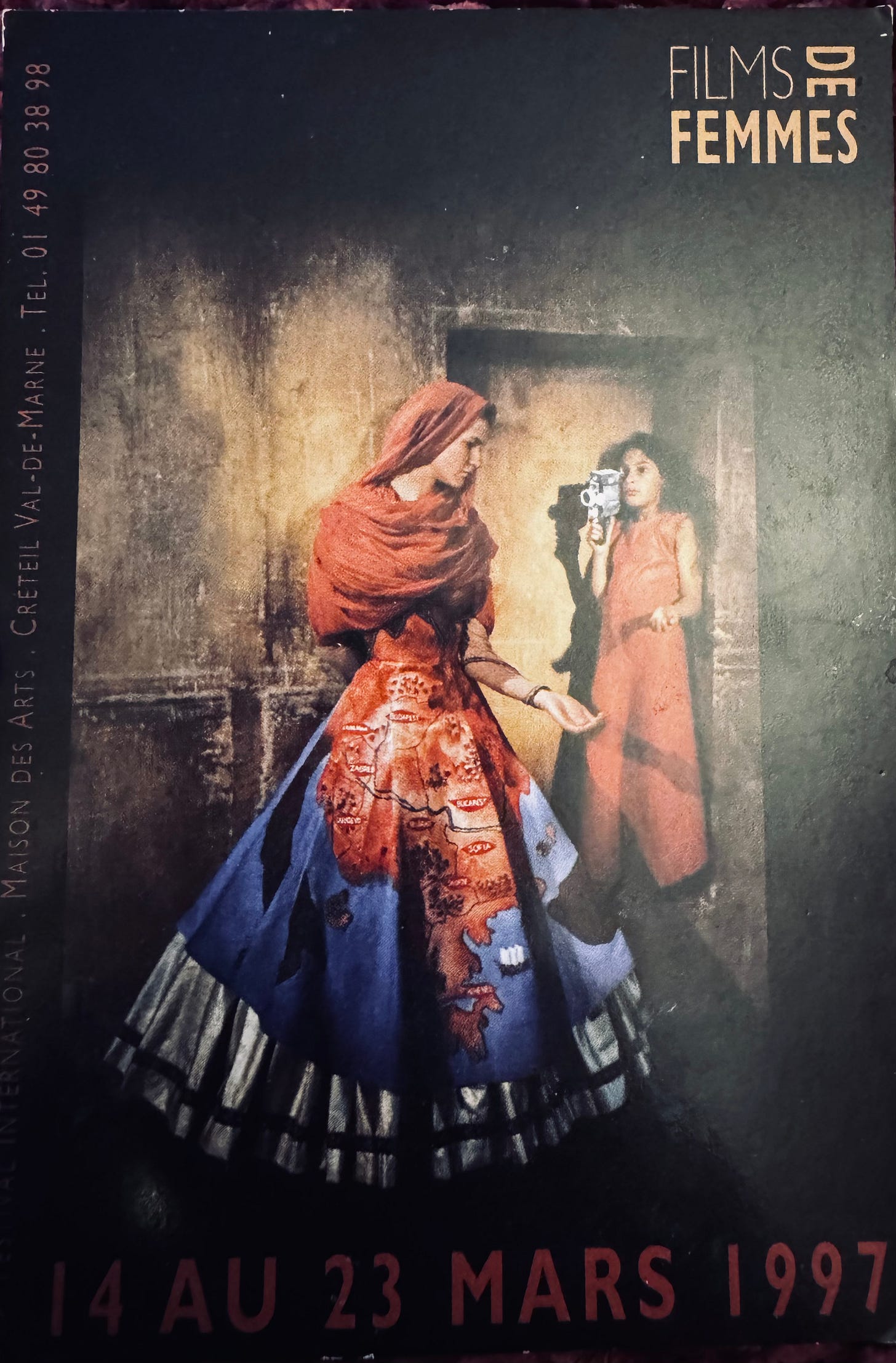

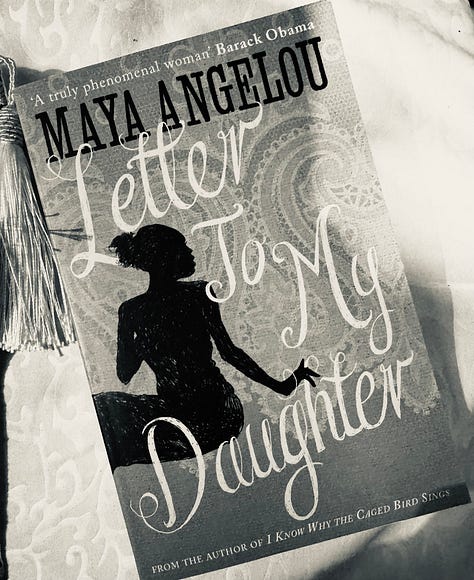

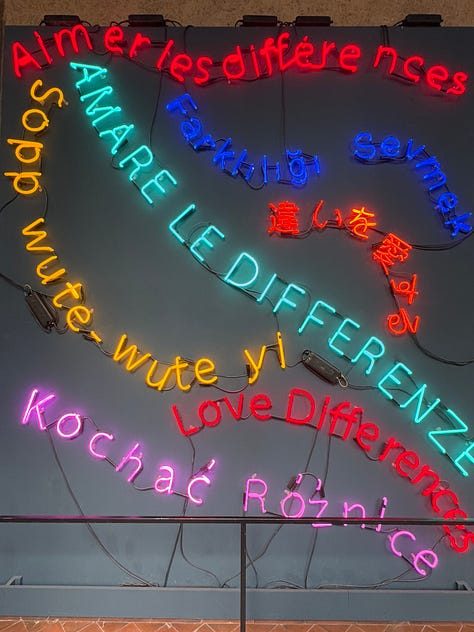

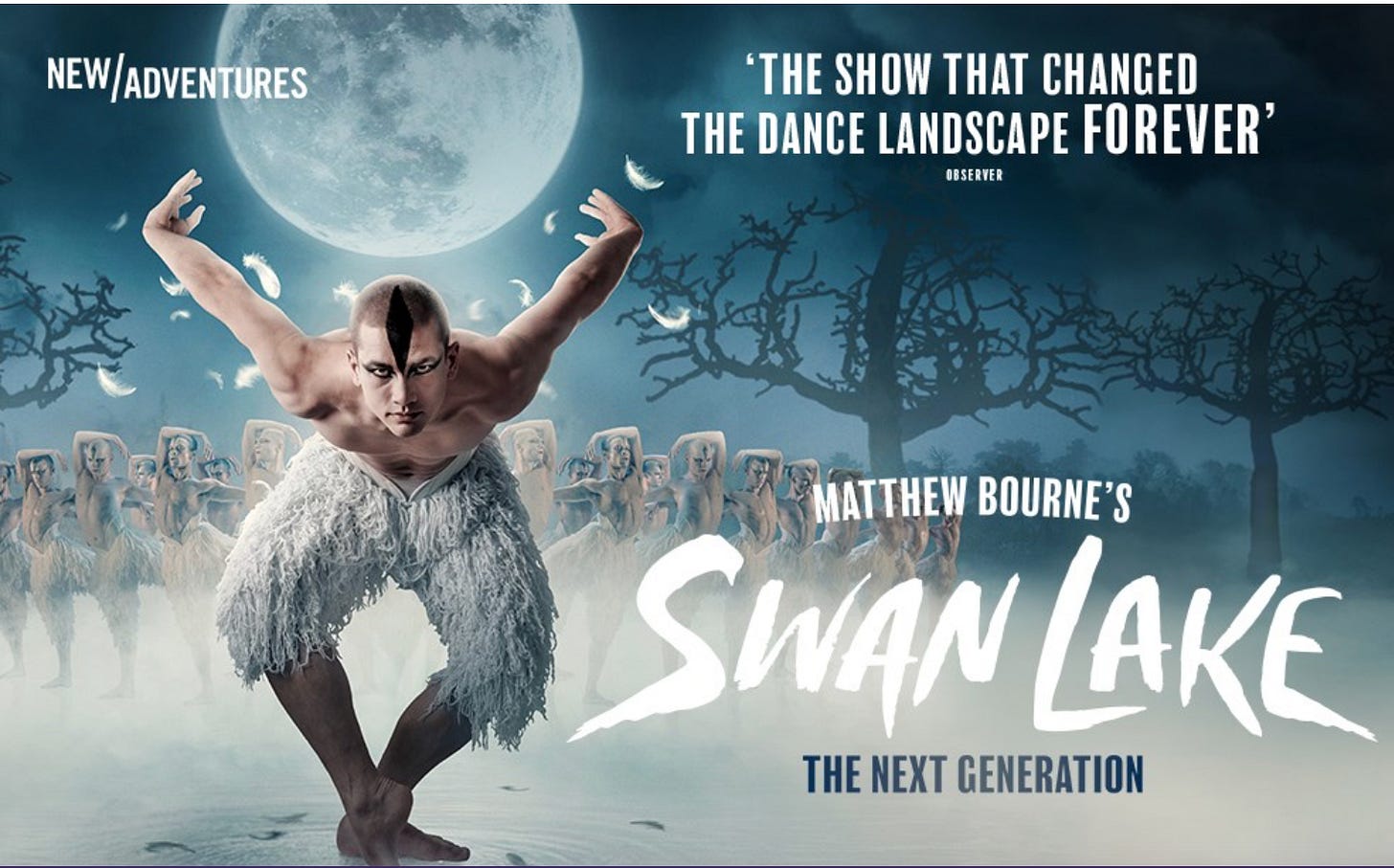

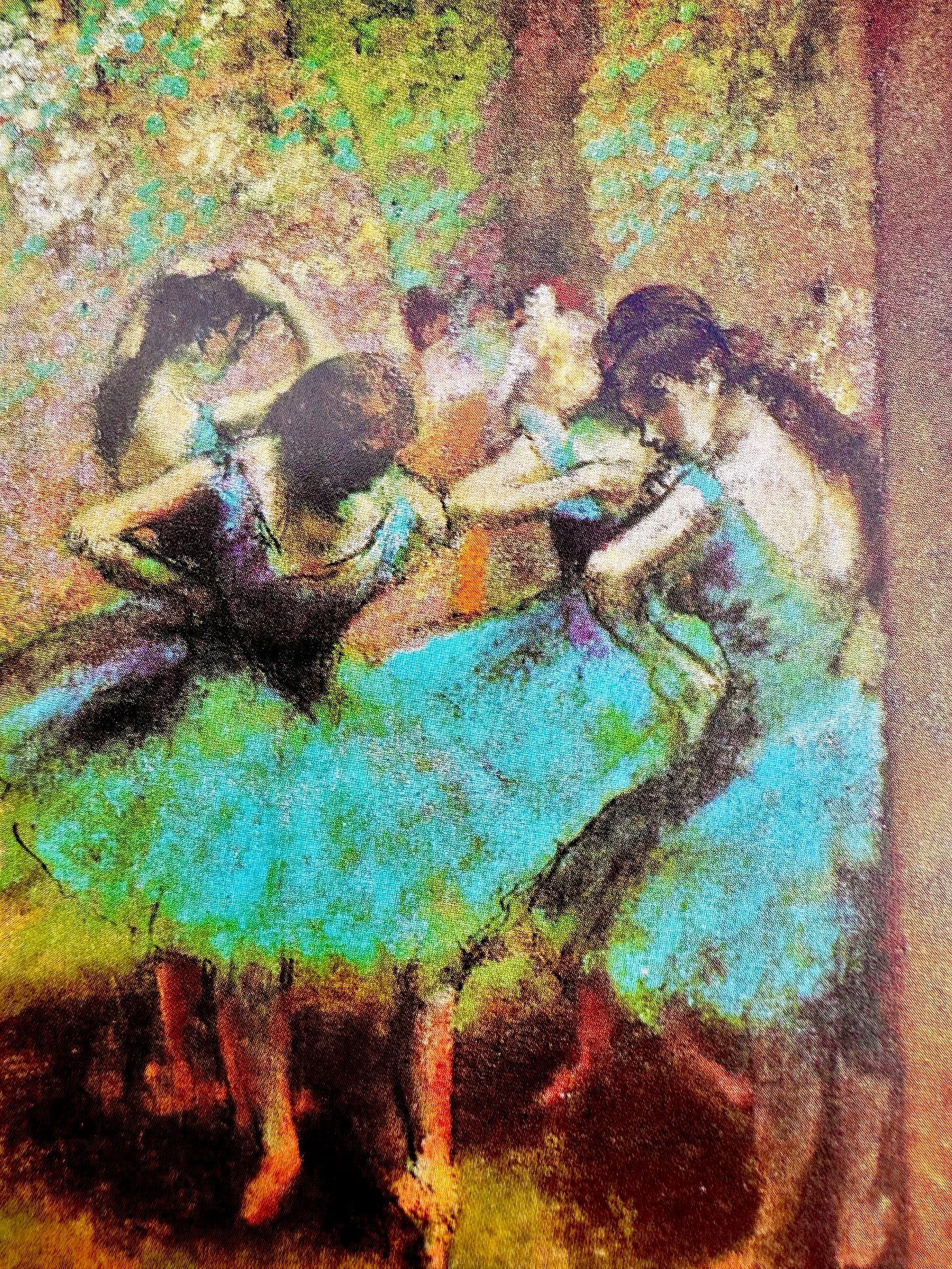

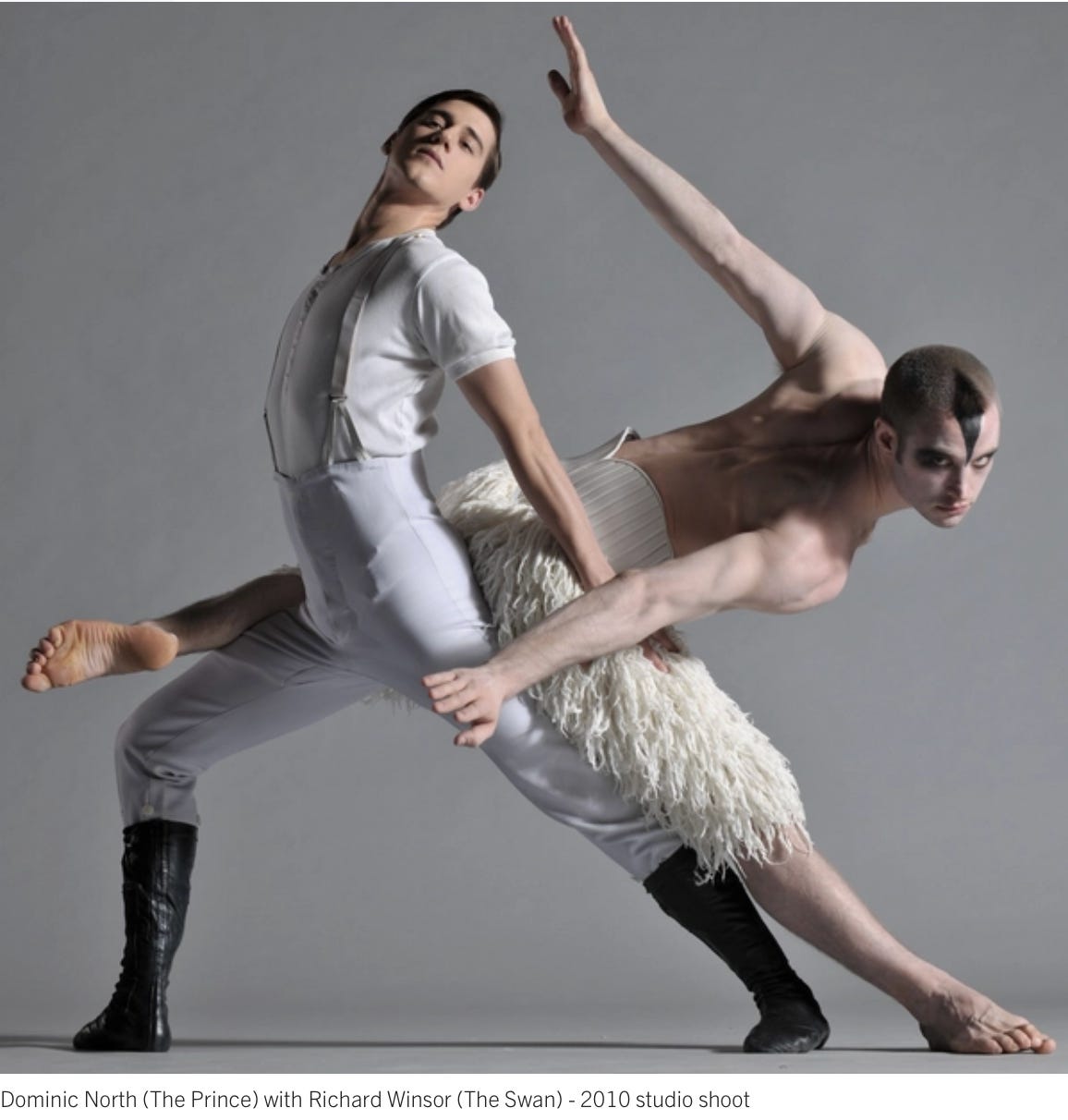

The 2nd, 5th and 6th images are from the Emotions Retold by Contemporary Art exhibition, Chiostro del Bramante, Rome (December, 2024).

Plurality of audience equals plurality of meaning. And so with creativity, comes great responsibility. Which is to say: creativity is power. ‘Art for art’s sake’ is therefore not only philosophically inconceivable: in our time and our places, it is actually undesirable.

Don’t get me wrong: I find contentious the idea of placing the burden of responsibility upon anyone’s creative shoulders. Anyone investing themselves in expressing their authentic voice should be free to choose, and choose freely. The actual impact of their output, the fluidity of its meaning, isn’t a compulsory requirement to agonise over in the process of making. I believe in freedom of choice and stand against any kind of dictatorial agenda.

And yet…

A few days ago, a friend of mine referred to a contemporary visual artist who, despite significant professional success and the inevitable exposure to worldly issues that comes with it, is a ‘climate-change denier’.

How can someone working in a relatively privileged context, in these increasingly complicated and urgent times, someone who has the power to spread word or image, be a ‘climate-change denier’ with any degree of integrity, even confidence? Today, when we see the devastating impact of climate change reaching ever more widely, ever more uncontrollably, year after year, season after season? When we see how it affects not only underserved nations vulnerable through lack of resources and protection, but also the crowned ‘glory’ of the ostensibly ‘immune’, developed world?

I’d like to think that ‘climate-change denier artists’ are a rare breed. That, instead, the world is full of creatives from all walks of life, who more or less deliberately advocate for everything and anything that matters to them and therefore to all of us. From the beginnings of time, creativity has leant into, carved or at least chipped away at, collective consciousness. This includes artists whose work is deeply, even obscurely personal. It includes artists whose work deliberately ‘resists meaning’: such intent is itself a comment for and about its times, all the richer for its adamantine persistence.

As Ancient Greek theatre or Shakespeare’s plays continue to teach us, the personal is always, inevitably, also political. Whether with fatal or comedic consequences, moral corruption in a leader will result in the suffering of the state and its citizens, while endemic prejudice can injure the most intimate bonds of trust. How we treat our kin is our cultural context in microcosm.

From identity politics to acts of resistance to meaning, every artistic choice is essentially political: a response of sorts to pressing social, environmental or personal issues.

‘Was it accidental that Degas’ women are always seen to their least advantage, with fatigue in their eyes - exhausted, heavy-limbed dancers, cleaning women hardly able to drag their heavy pails around? Was this denial of lyricism and expression of cynicism, or was it an expression of non-conformity which rejected feminine beauty along with convention?

François Mathey: The Impressionists and Their Time

We are fortunate to encounter, in our travel, leisure pursuits and daily life, all forms of creative talent - voices that engage with the world around them, whether deliberately or tangentially, timid or outspoken.

This publication, Beyond Beauty: Art and Intent, spotlights examples, individual or collective, from various fields of creativity and different cultural contexts, which have touched me through their sensibility to the vulnerabilities of their (and therefore our) time. An anthology of personal encounters, rather than evaluative inventory of ‘most successful’ or ‘best at’: because ‘art does not exist in a vacuum’.

Future newsletters (in no particular order, and subject to the elements):

From Echo-Chambers to Eco-Systems: Museums for a Vanishing World

Rhetoric for Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times

When We Dance

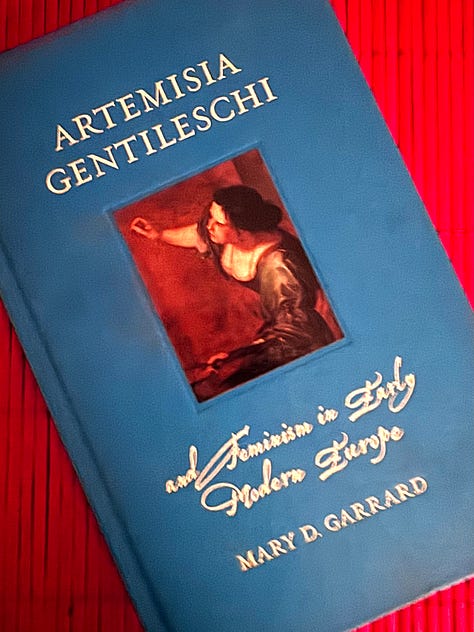

Old Masters, Never Mistresses: Great Daughters of Famous Fathers

Elegant Wit: the Legacies of Sei Shōnagon, Poet and Lady of the Heian Court (Japan 794–1185) and Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Medical pioneer, Travel Writer, Poet (England and Europe, 1689-1762)

Palestinian Embroidery

A Vacuum is a Bell Jar: The Sanctity of Knowledge

To this day, in most Western languages at least, the pronoun for ‘artist’, ‘writer’, ‘composer’, ‘conductor’ etc persists as male.

Such a great article! I'm impatient to read next ones. In all his shapes, art surround our ways of life.

What a lovely meditation on these encounters!! I'm so glad we "met"!