luminous places

light, lumière, licht, φως, luce, lumina: a polyphonic geography of wonder

It is easier to enhance creativity by changing conditions in the environment than by trying to make people think more creatively.

- Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

15 December, 2025: I’m about to embark on a predictable art trail which begins with the Eurostar from London St Pancras to Rotterdam. Normally at this time of year I return to the fold of Rome, catching up with friends over Mediterranean Christmas. Today’s journey is therefore a snap decision to leave behind the comforts of a (lovingly) haunting past.

At the first stage of passport control, I relax into the amorphous softness of ambient chatter as four distinct European languages converge into the polyphony of departure zones: a mother speaking to her son in Flemish, but turning to her friend in Italian. A French couple. I myself pass the time messaging towards three different parts of the world, including across the Atlantic.

The ornate underbelly of St Pancras International has become more than a geographical borderland: it’s a coupe of effervescent identities overspilling like New Year’s champagne, in unintentionally fizzy and unashamedly joyful erasure of liminality. My own sense of self slips out of its paradoxical bind the moment I hand over my British passport again, this time at continental (French?) border control; it assumes a lighter, less performative form than in daily life when I’m often subject to questions about my accent and/or ‘But where are you really from?’. Here I can relax into a sense of self shaped by relational acoustics rather than geographical assignation by country of birth (which assignation will forever label me as ‘other’ even after 70% of British lifetime). Anyone who has lived in more than one country will vouch for how exhausting it is to keep justifying who you ‘really’ are. To explain that ‘home’ isn’t a fixed concept. That all you want, when you look up, is to see the light of the same sky.

The polyphony of St Pancras eventually also floods the Eurostar. Passengers settle quickly into the microcosm that is their travel ‘group’, determined by seat number or social affinity. Small screens above the isle contribute to the party with animated visuals relevant to this journey, minimally captioned in Dutch, Flemish, English and French.

Other than as émigré/expat (depending on context-subtext) in mainland Europe and trips to the Middle East, my experience of travel is limited compared to that of my peers. And yet I only seem to relax in the liminality of journeys. Perhaps by now this is where I belong, in transit - where half-English half-Italian voice notes to friends don’t refract oddly off public walls. Where a Belgian grandmother, feeding grapes to the infant on her lap, smiles at me with understanding when I ask in a language she does not speak, if she’d prefer the window seat.

At Rotterdam Station, following a delay crawling out of Antwerp where ‘people were on the tracks’, everyone alights without saying goodbye to their companions of four hours. At first, I find this a little stinging - haven’t we, after all, just breathed 1/6 of a day in close proximity? But with hindsight I understand it as part of the shared flow: together we poured in and together we pour out of this train. We trusted its pull below the depths of La Manche while our experiences whirred in different tongues inside homely little tribes neatly distributed along carriages. Also with the momentum of flow we finally stood up, tugged our luggage off racks and stepped into the differently dynamic space of our destination. We parted ways.

Rotterdam station glistens with logical order, sleek cleanliness, the gloss of efficiency. Its unhurried demeanour is explainable in part by the automated ticketing service. Within steps from the Eurostar, I tap a slim yellow boulder with my phone to register use of the Dutch transport services; later, in Delft, I tap my way out of the circuit. There is not a queue in sight. But flow and efficiency are not just about automation: these were already characteristics of my experience in 2014 when I first visited the Netherlands and contactless wasn’t a thing. It seems to me that here flow isn’t a state of things as much as an attitude which results in this state of things: the Dutch sense of civic clarity comes across as more ethical than functional.

16 December: This morning I stepped into this view:

It’s not often that I find myself walking into a pop-up postcard at dawn. Perhaps a 5D one, if you count the measured pace of a modernised historical town in sync with the windmill watching over it; the outpouring of city bikes on ample lanes organic to calm roads where electric public transport provides swift, reliable transition; or the scent of an unusually soft December; the drone of a cleaning truck along the canal that skirts a train station sumptuously designed, studded with starry lights.

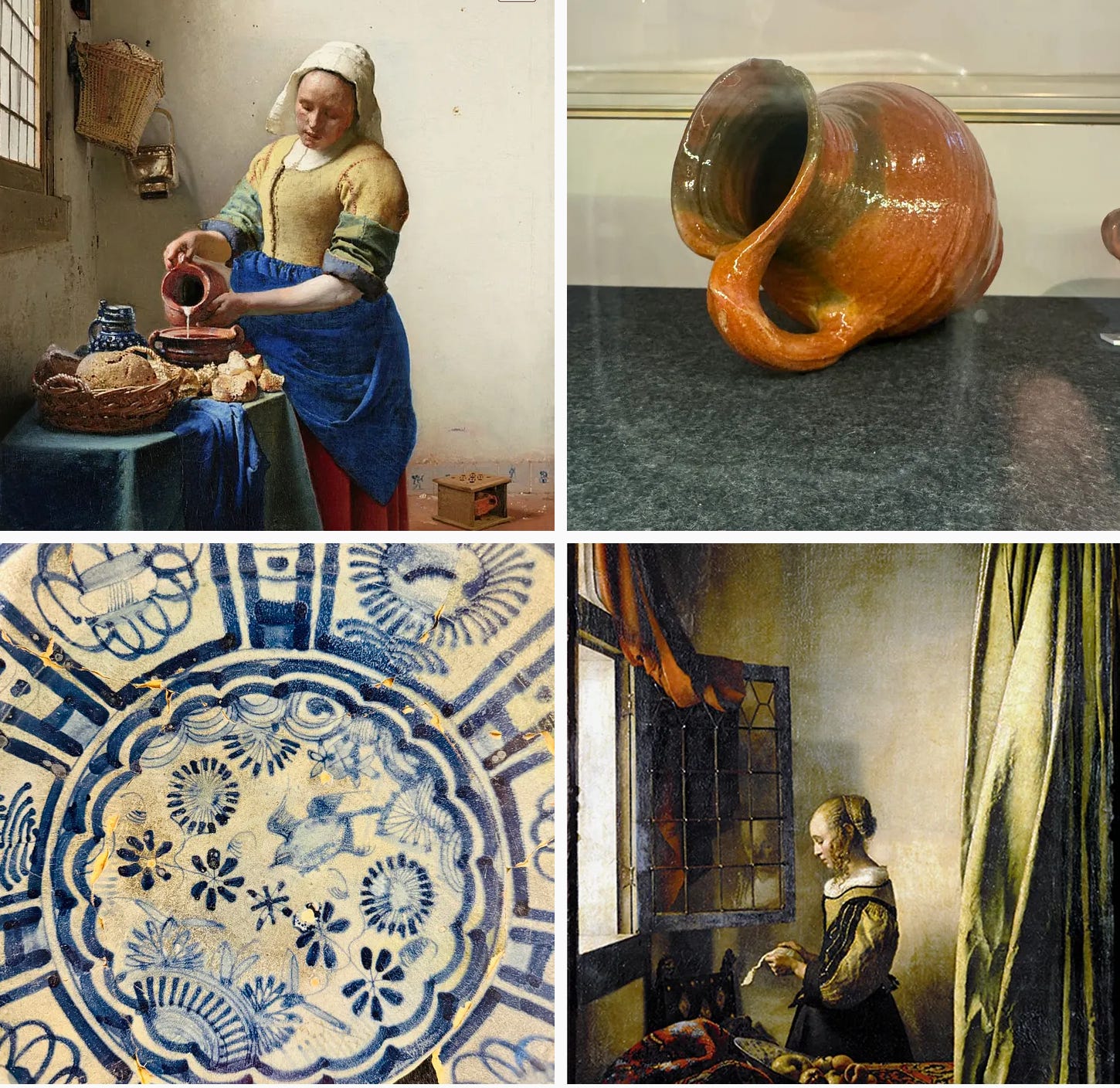

The spirit of some places really gets to me. This one squeezed tight in my ribcage all the way through the day. It held my hand at Vermeer Centrum where I found myself buying the ticket in English but asking for a tour device set to Italian, which I then switched to French. And something had to hold my hand - not only on the first floor, where I was moved by the science of Vermeer’s palette, the reconstruction of his domestic backgrounds, the pottery items from private archaeological collections so we can see for ourselves, multi-dimensional again, the milkmaid’s jug, or the letter-reader’s Delft blue fruit bowl:

I enjoyed messing around with scenery sets and demonstrations of how The Master of Light captured translucence and luminosity.

But on the second floor the caption on the wall stopped me in my tracks before I even saw its object of reference:

To mark 350 years to the day of Johannes Vermeer’s death, contemporary local artist René Jacobs re-created View of Delft out of 110,851 miniature human figures representing the estimated population of the town on 15 December 2025. Each figure was added by a Delft resident: the first by the oldest, and the last, on 12 December, by a pregnant woman (baby due 15 December). The resulting work, We are Delft, is thus a 21st Century installation - self-reflexive meaning-making in material form across time, but anchored in place. A gesture that erases polarisation1 by embracing both diversity and heritage. Under Jacobs’ watchful eye, past and present reunite, holding hands in a movingly resplendent dialogue that celebrates continuity of creative expression, from a certain resident of Delft named Johannes Vermeer, who set to work on this townscape around 1958, to today’s residents living and breathing the same air. One glance is enough (try it even with the reproductions here) for the sonorous energy of these three dimensional images to vibrate kinetically. This crowd is dancing.

I had not set out from England on 15 December 2025 specifically for Vermeer’s commemoration - I don’t tend to keep up with special calendar days. So the poignancy of my arrival in Delft on this very date was heightened by the finalisation of We Are Delft on 12 December, a day of particular significance to me, which essentially facilitated this journey in the first place. The force of such coincidences is hard to ignore.

Having stocked up on Vermeer stationery with all the restraint I could muster, I set off for the Hooikade, where the great man stood to paint his original, that is to say, subjective, interpretation of View of Delft. I have no words for what it felt like, being right there, at one with his own skyline. What with the shroud of cliché that threatens to demolish most luminous moments when they transition from imagined to experiential, it would be best just to say this: I felt the past and the present (my own, and of this place, its people) converge as a physical sensation that pinned me down. I spent a long time writing and photographing as the light shifted - subtly at first, then more dramatically, and yet without ever reaching the luminosity of Vermeer’s own moment in time. Later I learnt exactly why: this was the wrong season.

As reported in the Smithsonian, in 2020, in yet another momentous encounter between art and science, astronomer Donald Olson ‘studied the 17th-century cityscape’s depiction of light and shadow’ in Vermeer’s View of Delft, ‘to pinpoint the moment that inspired the artist down to the hour’. Taking into account architectural, cultural and ecological context down to minute detail, Olson concluded this masterpiece was most likely completed ‘around 8 a.m. on September 3 or 4, 1659 (or the year prior).’2

Gratitude, quiet awe are just two of the defining emotions triggered by my time in this place. And there’s also the realisation that my ‘luminous’ experience on the Hooikade was the cumulative effect of immersion, of love even, invested in a lifetime of encounters with art and in a variety of cultural contexts. Significantly, all of these encounters had been dialogic, never siloed, experiences. Even as lone observer in museums in countries where I didn’t speak the language, I could never be actually alone, empirically or metaphorically.

Similarly, it is virtually impossible to be working on a creative or innovative goal without being inevitably connected to (directly responding to, or addressing), others. Csikszentmihalyi actually insists that without an evaluative audience, an outcome cannot truly be defined as creative, just as nothing that we make is ever produced separately from everyone else and from the context ultimately shaped by all of us.

We Are Our World. Our world is us.3

While I didn’t come to Delft specifically to look at how Vermeer painted light, when I try to entangle the circumstances which brought me here, the little patch of yellow wall that pulled me in this direction immediately revealed itself. I guess if one could single out a colour in this entire painting that ‘catches the light’, it would have to be the yellow.

Moreover, even under the muted grey and beige of this mild December in 2025, it is light that keeps stopping me in my tracks. Not only as natural phenomenon or as captured by a masterly paintbrush - but also as function of cultural permeability. Dislocated from the many places I’d call home, I feel free. Free from labels imposed upon me based on appearances, and from labels I myself seek - to neutralise those appearances. The light I breathe here doesn’t so much dissolve boundaries (physical, experiential, disciplinary) as liquefy them into a state of osmotic flow. I realise that on such currents, through exposure, attention, and the willingness to be moved - by that and by those around us - by positioning ourselves in a receptive state, we can finally drift into presence; we can be altered into being - as opposed to doing, yearning, seeking.

In ‘Art as Therapy’, Alain de Botton evaluates the potential of art - of our encounters with works of art - as prism for self-knowledge and for re-sensitising ourselves to the beauty of the ordinary; a means towards counteracting the perpetually dissatisfied hunger for the unattainable. Meanwhile, on the other side of the creative process, there is discovery and meaning-making - not only through art but through any expression of human ingenuity. So, from whichever point we view it, the outcome of creative endeavour becomes the nexus for the permeability needed to feel ‘more fully alive than in the rest of our lives’.4 And therefore truly free.

If we take Csikszentmihalyi’s proposal that a creative outcome ‘arises from a synergy of many sources, not only the mind of a single person,’ then my Delft encounter was the pinnacle of convergent streams, all of them contextual. By engaging in cultural experiences - in conversation, writing, even just thinking - we are already contributing our own modest ‘human figure’ to the choreography of cultural heritage at large. Csikszentmihalyi’s proposition that nothing we create is ever really new, isn’t because influence is unavoidable but because, he argues, the best innovations of humankind have to be re-learnt - studied, expressed, re-expressed, applied, then seen again through new (usually updated) lenses. ‘The spark is necessary,’ he writes, ‘but without air or tinder there is no flame.’ Writing can be tinder. Looking, standing face-to-face with someone else’s creativity- or even better, contributing to its revival, like the people of Delft- is tinder. Or, in the words of Tom Stoppard, our recently departed giant of intellectual prowess and creativity, ‘we shed as we pick up’: knowledge, discoveries, innovation, artistry.

17 December: I’m here to take in my view of Delft for the last time. In this version, the sky is overcast, the canal glassy with the indubitable stillness and flawless reflectiveness of mirrors. No ripples, no gilded shimmer. People rushing past (mostly students on their way home), don’t stop for homage to pale winter light. This vantage spot being more than familiar, they might have understandably become de-sensitised from what I, as outsider, regard with wonder. The shifting perspective, the fluid, luminous view of their town. It will probably take a trip away from home, somewhere into a differently-cadenced space of light, for them to be awe-struck at the polyphonic potential of place, of time, of being.

It seems that, although it takes displacement to restore us ‘home’ to ourselves, even if we do all we can to release the past, our lived context - in its entirety - will insist on highlighting our perception of the world down to its tiniest detail. Without palimpsest of context, there’d be no grounding in self, home or community - no ‘yellow wall’ to catch the light of heritage.

18 December: At the Mauritshuis in The Hague this morning I saw many wonderful things about which I will write another time. Just one last thing before I sign off: standing in the very spot where Proust’s Bergotte collapsed before the sight of Vermeer’s View of Delft, in real life proximity to its palette, I can confidently contribute to the yellow wall debate that the only true patch of ‘yellow wall’ in this painting is this:

My point is backed up by the wholesome, yolk-yellow 21st century risposte to the debate, visible today from the Hooikade and resplendent with enlightened wit. Dedicated to Vermeer, Proust, Bergotte, Jacobs, the people of Delft and its visitors - the creativity chain shines on.

‘René invited all Delft residents to add their own figure, creating a work that brings everyone together - without polarization […] 4,000 Delft residents […] pasted “their” figure. (Vermeer Centrum, Delft - display)

I developed this in Art and Intent.

Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, The Psychology and Discovery of Invention , Harper Perennial Modern Classics, 2013

Thank you for reading it :) I hope not too clunky, there was so much I wanted to say and do with this but equally had to avoid getting carried away for readers' sake :)

We live in an ocean of time, where events, things, and people are continually succeeding one another, but we cannot live with such boundless complexity, because we disappear in it, and therefore we organize it into categories, sequences, hierarchies. We organize ourselves - I am not nameless, my name is such and such, my parents were like this and that, I went to school in such and such a place, I experienced this and that, by character I am like this and like that, and that has caused me to choose this and that. And we organize our surroundings we don't just live on a plain with some grass, bushes, roads, and houses, we live in a particular place in a particular country with a particular culture, and we belong to a particular stratum within that culture.

All of us sum up our lives in this way, that is what we call identity; and we sum up the world we inhabit in similar ways, that is what is called culture. What we are saying about ourselves fits, but no more than if we had said something entirely different, thought something entirely different about ourselves and our place in the world—if, for example, we had lived during the Middle Ages and not in the early twenty-first century—and it too would have fit and seemed meaningful.

That identity and our understanding of the world at one and the same time fit yet are arbitrary is, I think, the reason why art and literature exist. Art and literature constitute a continual negotiation with reality, they represent an exchange between identity and culture and the material, physical, and endlessly complex world they arise from. - Karl Ove Knausgaard, Inadvertent