visible strings

the weird and wonderful paradox of creativity as a means to power

They found it amusing when I said I'd skip the mountain hike for a marionette show.

I’m the only adult unaccompanied by a child. When the cashier shows me Seat 4 on Row 3, one of the last available on the map of a diminutive auditorium, I tell her it’s perfect. ‘But … close to the front!’ she warns, taking payment. I couldn’t be happier.

I remember this auditorium as rows of perhaps ten wooden benches. When the doors open the attendant pulls across a velvet cord, at once delineating and dissolving the boundary between the real world (bright sunshine, cobbled sounds of street life) and the hush of magical sanctuary (the stillness of the stage). While too early to enter, it’s the right time for the mental shift. The dimmed lights, carpeted floor and plush beige chairs replace the benches of memory, telling me this womb of stories has enjoyed an upgrade. And then my breath catches - not so much for cut-out memories of crude miniature worlds of plywood or polystyrene, as for a specific festive occasion.

In most cities beyond the Iron Curtain, even when basics such as food or electricity were scarce, places of cultural provision and physical exercise thrived on rigorously active programmes in designated venues, alongside communist party headquarters, the Pioneers’ Palace (youth organisation for hobbies and activities), sports stadiums and training centres. Like other large Romanian cities, Brasov had the full suite of what is still known as ‘intellectual and artistic’ entertainment: the Opera, the Philarmonic Orchestra, the Drama Theatre - and for the youngest audience, the Puppet Theatre.

Smaller towns would boast a minimum of two such institutions. If a designated space was lacking, a Cultural Centre hosted touring companies from the city. The pervasive presence of these dogmatic but wonderful institutions was part of the Soviet script - the USSR imposed a regime of culture and sport to its vassal countries, fundamental to the propaganda machine. It then stipulated what culture and sport should look like.

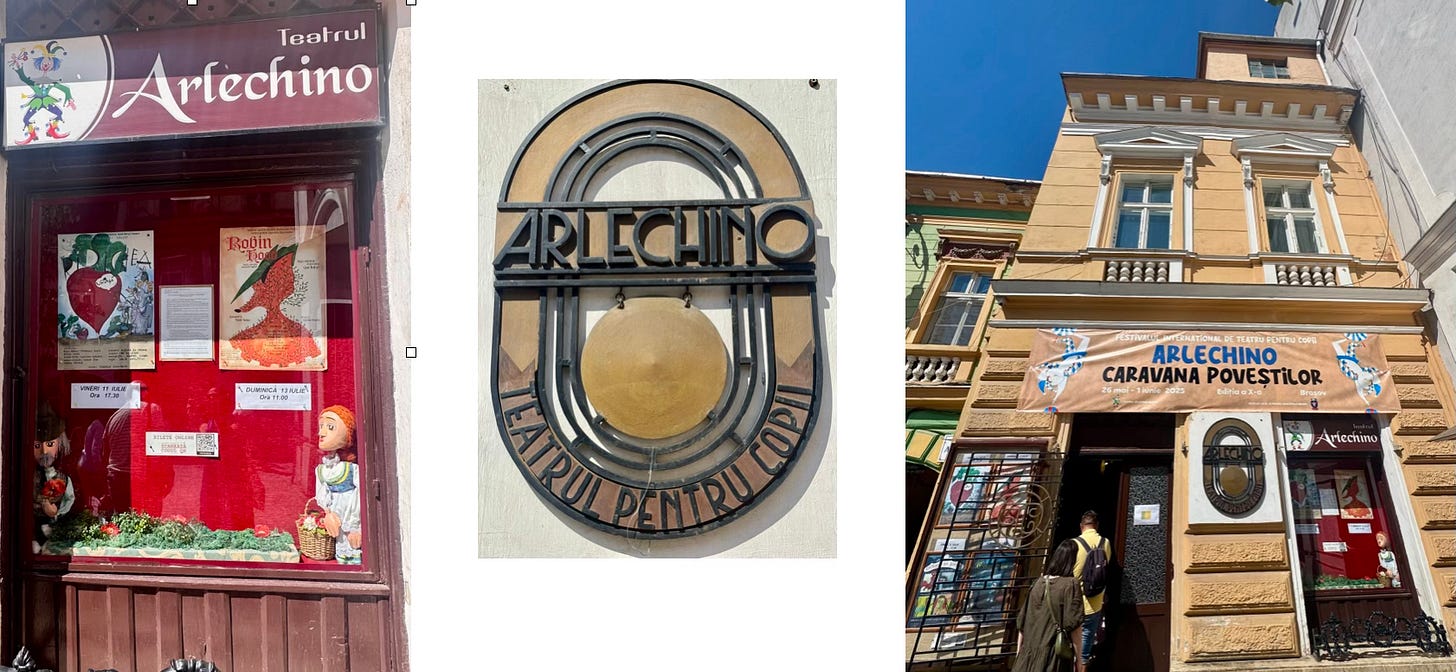

Arlechino has always operated from a small building in the historic centre, adjacent to the main piazza. Communist workplaces of the 1980s, from factories to institutions, organised Christmas gift-giving for the employees’ children. Following a stint as factory engineer, my father worked as sound technician at the Drama Theatre of Brasov. In a city of colourfully historical architecture this theatre presides over a busy main road with its discordantly functional character. For the children’s gifts, the quaint puppet theatre stage was somehow more appropriate. It’s important to note that this was no Christmas party: there were no games, no festive mingling, no music. The children, lined up with their parents on little wooden benches would be called up to the stage one at a time by an ersatz Father Christmas to answer ‘yes’ to questions such as ‘Have you been a good boy/girl for your parents this year?’ and ‘Are you working hard at school?’ Looking back, I see us all as little automatons marching shyly towards the little (but oh so big!) stage, overwhelmed by the occasion (and perhaps also by these public declarations, true or untrue, of our worth).

Pre-communist Santa was known as Moș Crăciun, literally ‘Old Man Christmas’. But back in ‘those’ days, Father Christmas went by his Cold War name, Moș Gerilă, loosely translatable as Old Man Frost - or, as I’d prefer to translate it for the more accurate, duplicitous connotations, Old Janus. The Roman god Janus (father of ‘January’), was associated with beginnings, transitions, endings. Our own Janus’ double face looked both towards the New Year and away from it, unashamedly vigilant and intrusive. During the Cold War, the dextrous Soviet upper hand scripted a secularised version of Christmas for all countries east of that heaviest of curtains. This meant that gift-giving and celebrations were re-cast as atheist end of year festivities.

Yet despite state intentions, in their own homes Romanians carried on celebrating Christmas on Christmas Eve. Until the overthrow of the dictatorship on 23 December 1989, for most families Christmas was hardly a feast, stripped of both spiritual and material dimensions: the former was forbidden, the latter unattainable. An anachronistically pagan feel was preserved instead, of value fully focused on nuclear family togetherness: decorating, baking, cooking, eating - a sort of rationed bountifulness, especially in the latter years of austerity. The more fortunate kids enjoyed the gift of an orange or a bunch of unripe bananas. There was no extended family and no church time, no St Stephen’s Feast/Boxing Day to indulge in some more afterwards. Nor were there carols, although a series of gorgeous, viscerally pagan folkloric rituals (pre-dating the Roman invasion of Dacia), took place in every community on New Year’s Eve and Day. All this to say that those gift-giving events for children of employees were therefore pretty exciting.

Culture, the lush fruit of creativity systems, besides providing opportunities for existential contemplation and life-affirming joy (and tears!), has a steely potential to control and dominate. Communist propaganda is particularly effective because of the centrality and accessibility of its carefully orchestrated events of immensely entertaining, didactic and motivational power. In Ceaușescu’s Romania1 these didn’t only take place on designated stages but also on streets and stadiums.

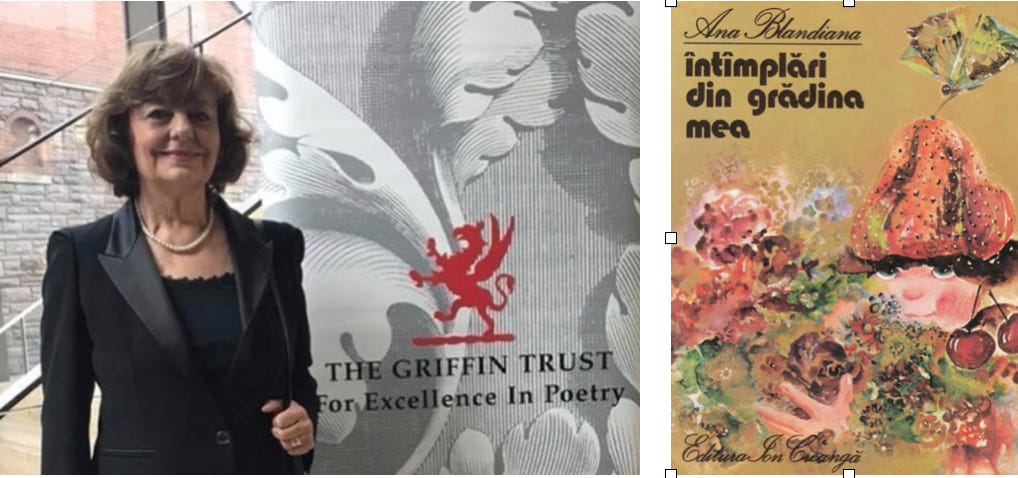

But in the worship of a Father State, didacticism marches hand-in-hand with censorship. In the case of children’s theatre and literature, the artistic ignorance of over-stretched state censors2 ironically facilitated dangerously delightful subversive messaging: ‘approved’ innocent imagery could easily be exploited for and by adults. All the more so on stage, where the very art of manipulating a puppet is a symbol of control, and the experience of the medium safely ephemeral. Other notably daring under-cover messaging for adults featured in the work of Ana Blandiana, one of the greatest Romanian writers and activists. Her most risqué tale in verse, ostensibly about a tomcat named Asparagus, implicitly critiqued the autocratic personality cult. Blandiana was eventually banned but post-Revolution her courageous activism and artistry returned to flourish and inspire her now grown up audience: she founded and lead the Civic Academy while at the helm of several other institutions fundamental to the re-birth of democratic culture in liberated Romania. Her oeuvre includes numerous volumes of poetry, essays and fiction. As a child I was blissfully ignorant of the politics at the heart of my copy of Tales from My Garden, but many years later I had the honour of meeting Blandiana at an Irish-Romanian poetry event in Belfast (1996) where she collaborated with the great Seamus Heaney.

Meanwhile, propaganda succeeded marvellously as inspiration for some of us children. I confess with blushing horror that I enjoyed pioneers’ marches and stadium choreography (the fun of waving red carnations or miniature patriotic flags…!) in celebration of socialist festivities such as The International Day of the Worker (1 May); Liberation [from fascism!] Day (23 August), or visits by the president to our town. These were opportunities for togetherness, band music, colourful dressing up (albeit hundreds of us in identical costumes to spell out patriotic slogans in giant white, red, yellow and blue arrangements on a stadium), even the occasional street seller of yo-yos (cloth balls stuffed with saw-dust, which we treasured from one year to the next) and cockerel-shaped lollies of burnt sugar. With everyone off work and school, these felt like the special occasions they were intended to be. As kids we never questioned the effusively militant celebration of bountiful crops, factories, and so-called ‘international’ success, clearly incongruous with our empty fridges or the glow of oil lamp on homework ink. Our parents were too scared for their livelihood to break the spell of this particularly magnificent show.

I’m shocked and amused remembering the fun we had on the communist stage; at how much closer to fascism it was even as it fancied itself the polar opposite; at how we performed its scripted games - unquestioning kids, frightened adults. How we worshipping the Father of our state on cue, in loud, confident voices, with flags, slogan placards, and human formations in pretty patterns.

Wonder is, unavoidably, undercut by the kind of access to material (but perhaps also to social and spiritual) comfort we take for granted when we live in a privileged world: there is nothing awe-inducing in choosing a bunch of bananas or a bag of sugar at the supermarket, or in stopping by a convenience store to grab some chocolate on the way back from work. By contrast, frugality and deprivation are engines for wonder: when something good turns up, the human capacity for joy and gratitude reaches levels otherwise reserved for epiphany and miracle. It is a cruel blessing, the miracle of access to basic livelihood.

With the unexpected tactical benevolence of a tormentor’s hand, or maybe just more luck than other communist countries, Romanian culture was not all propaganda: it saved a place for ‘safe’ classics, including international. I enjoyed countless theatre shows especially by accompanying my father on tours. The long, exhausting, uncomfortable coach trips in rusty vehicles that stunk of diesel and made me travel sick were worth it: I’d get to see that play one extra time. These were also rare opportunities to see other parts of the country, albeit within the parameters of coach/car-park/venue.

Occasionally the Brasov troupe would perform in towns so small they’d barely qualify as villages today, in dingy halls lit by a single fluorescent strip. There was never a raised stage or curtains, and the auditorium consisted of rusty, fold-away plastic chairs. These sparse settings were in fact the very reason my tween self watched in awe how the stage crew deftly set out a minimal scenery grown out of the mobile features of permanent sets I knew by heart. It didn’t matter that the backdrop of a beloved performance was reduced to its backbone: that it still worked and was applauded all over again, made it a thing of wonder. After all, the more effort we put into filling in gaps, the closer and richer our experience of a work of art.

These tours could be why I particularly enjoy teaching The Seagull, a play of deeply human, distinctively Chekhovian, pre-Soviet, concerns. The Seagull opens with two minor characters building a makeshift stage for the play-within-the-play that sparks off the main plot. This experimental mini-play becomes a symbol for the risk-taking creativity vs power dynamics conflict of the main play, pitching modern and traditional values against each other against a wrenchingly beautiful décor of social change.

By contrast, I never deliberately choose to teach As You Like It for fear of turning rewarding memories of Shakespeare in performance into assessment topics. I saw As You Like It over 18 (counted) times, and knew it word for word, in Romanian. Ironically, Shakespeare is much more accessible to foreign audiences because translated in their own, contemporary, language. By contrast, my English pupils depend on my assistance with textual paraphrase (or No Fear Shakespeare!) However, since decoding Shakespearean semantics and syntax is not only fun but proven to have cognitive benefits,3 as teachers we focus on enabling pupil resilience and curiosity in decoding Shakespeare. Ideally, they should reach the stage of ‘reading’ rather than ‘translating’ - a challenge in the classroom since the meaning of a play relies on non-verbal cues.

For years I could recite entire scenes from As You Like It and, with a little help, the full play. This was very useful when short of games to play in a toy-less home. Like Bottom in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, I readily jumped to adopt more than one role on the living room carpet, our stage. I still cherish vivid memories of the actors playing Rosalind (‘Rosalind’ was also Nina in The Seagull), Orlando and Celia; of their costumes, especially run-away Rosalind’s ‘safety disguise’ as sylvan male youth as she chases Orlando unchaperoned in the Forest of Arden.

As I peer inside the diminutive auditorium of the Puppet Theatre today, the usher unhooks the velvet rope, offering a look at the dormant stage. There is nothing uncommon about my nostalgic curiosity: the city, especially in summer, swarms with expats hungered by an emotive quest as we return to our native land to savour so much more than cuisine. With a few more minutes to spare, instead of joining the parents and grandparents waiting with their little ones on the lobby bench, I pass the time taking photographs.

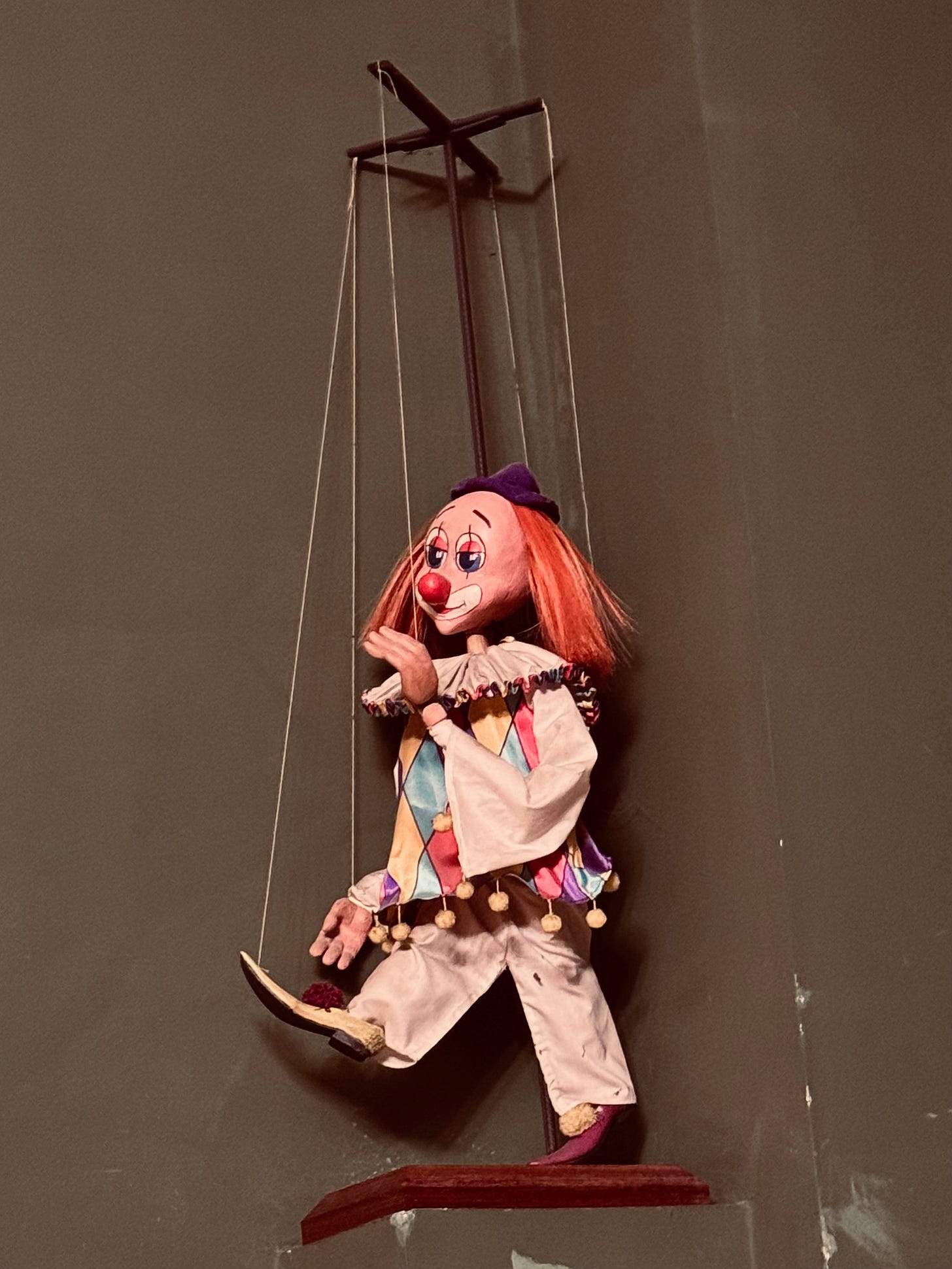

The preserved puppets seem younger than those of my day. They are also very different from the puppets which take the stage after the opening gong.4

Yes: a gong! I cannot remember the last time I heard a gong signalling the start of a show. Much like Tibetan bells or singing bowls, it didn’t so much call for a hush as mark a moment of transition from earthy to spiritual realm. Imagination is as close as one comes to transcendence in a totalitarian state, and I’m living this visit as if back in time. When the tall elegant woman next to me gives up her seat to allow a little girl to settle beside her sibling, I realise that many families are split across the auditorium. When the gong sounds once more, there is further shuffling as confused small children and kindly adults re-arrange themselves in more appropriate seats. The little girl leaves her newly acquired chair to squeeze into her sister’s chair, beside her; next to them, two other girls are also sharing a seat. They too are small enough to fit in more than comfortably.

This liminal moment - the second gong that settles the seat swapping - brings me an awareness of the cultural and historical richness of the narrative about to unfold: firstly, the earliest versions, A Gest of Robyn Hode (ballad, 1400s, cca 13,900 words) and the novel adaptation by Howard Pyle, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood (1883, cca 80,000 words). Then the translation from English into Romanian and finally distilled ‘from page to stage’ into a 45 minute experience of its most meaningful and entertaining essentials.

There are also the modulations specific to the experiential and ephemeral nature of the genre. Puppet shows often make a point of grounding the event into its human dimension before drawing us into suspension of disbelief. Here, firstly the human actors leap on, one character at a time, to divulge a contextual morsel. Their respective mannerisms warm us up for the puppet protagonists whose embodied experiences they will conjure. The audience is transported into the enchanted world beyond the Fourth Wall5 by the joyous musical energy of these larger than life humans clad in unsophisticated, even generic sylvan (again!) green and brown doublet and hose. They remind me of Rosalind and Orlando’s costumes in the Forest of Arden decades ago. Young and old, already excited, we connect to the unique timbre of their voices, agile body language, expressive eyes and mischievous smiles. I notice that these adult woodland thieves wear no make-up, how this renders them humanly close. There is no obtrusive artificiality - colourful outlines are reserved for the puppets (not that they will need help securing our focus!)

We clap energetically to the beat of the actors’ bouncy prelude but the truly exciting moment, born out of the silence they leave behind on the stage, is the entrance of the first puppet: a plump, monkish badger, modest in brown hessian, carrying a cross-body satchel. His presence instantly sets a tone that anticipates the moral of the tale: the ordinary people of this world are the protagonists of the show. By the time Robin Hood – a brightly anthropomorphised fox – and little John - a kindly teddy bear thief - enter, we are hooked.

The language they use, especially the sympathetic references to the poor they help with their infamous thievery is archaic, but I'm certain the kids in the audience understand it, whether by working it out or from bedtime stories barely stylised in contemporary re-tellings of classics. I'm really enjoying myself by this point as I sink into the comfortable familiarity of a language which has been eluding me (or me, it) for years. The phoney king /wannabe usurper /bad, bad dictator, regent prince John, is a bright orange tiger with skinny anthropomorphic legs clad in red tights. He wears adorable golden shoes and sucks his thumb – a didactic plot addition to help parents fighting a losing battle against this ancient self-soothing habit.

I’m mesmerised by the deft manipulation – actually, choreography – of the stuffed toy marionettes6. Each is animated by two sets of human hands and one voice, that of its ‘master’. The practised expressivity of a puppet’s body language depends entirely upon the dexterity and inventiveness of human fingers, a skill likened to playing the piano7. The actors must also feel and enact the puppet’s inner life while simultaneously suppressing their own impulses. This is why, despite immobile toy faces of strong, fixed features, there is no detail of body language and emotion, great or small, a puppet cannot express. It is this convincing illusion that draws our attention to it: the utterly unreconcilable paradox of watching ‘conscious’ behaviour in an inanimate object. Through neural mirroring, the puppet’s thoughts and feelings are also directly sparked in the audience. Try focusing on the human behind a puppet, and you’ll feel the instant cognitive pull back to the ‘conscious’ thing! It is a very intense experience.

Stripped of violence and frightening conflict but sophisticated enough to pitch good against evil through acts of justice and charity against greed, the entertaining show is enough to inspire moral questions relatively complex for a small child, such as stealing from the rich to help the poor. I finally see how this play, a classic on the children’s stage, spoke bare-faced and direct against the veneer of Ceaușescu’s tyranny.

There is a playful touch of medieval romance in the Golden Arrow Contest and in Maid Marian’s role which enhances the moral through her choice of winner and therefore husband. Just as with Rosalind, Orlando and other couples in comedies Shakespearean and beyond, the status quo is decidedly re-affirmed by the marriage at the end. Here, with it, the ordinary people are restored to power. So when the glitzy giant puppet of the rightful king, Richard Lionheart, enters the stage near the end of the show, I’m rather taken aback: why do we need him, here? Now?

The majority of words addressed by Maid Marian to Robin take place during the proposal and regard the alarmingly high number of children she desires from their union. Her giddy maternal ambitions are comically worrisome for Robin and for the adults in the audience, but deeply affirming for the children, who giggle delightedly, feeling wanted, valued. In the wake of resolved moral conflict, we clap joyously as the show ends.

In reverse to the opening, each character enters to bow their leave as puppet first, then as human. I appreciate once more the unpainted faces of these wonderful people whose vocation is to enthral the youngest generation not yet fallen prey to Screen Time and (surely totalitarian?) AI. Since we have come a long way from the days of magically growing cardboard flowers from behind a tiny stage set, from tape-recorded voiceovers to cover staff shortages, I want to know more: I want to ask the actors about their own memories of theatre, the places they tour, the shows in their repertoire, and do they visit hospitals and orphanages?

But it’s almost midday and they are due their Sunday rest. I step out into the bright city sunlight feeling more settled than I’ve been for months. This hour of time travel has unravelled in the guise of a language I thought slipping from my grasp, through the re-telling of a narrative originally from my second tongue, this one, of my adoptive country. Art has yet again stitched the rags of torn time into something rich and strange.

I wander into the Cultural Centre next door looking for the room where I once auditioned for rhythmic gymnastics (the selection of kids for any physical activity including non-competitive was rigorous). Up the grand marble staircase, I’m absorbed into a crowd of parents setting loose children dressed smart-casual, slightly older than those who watched the puppets. Puppy-fat cheeks, confidently smiling, these boys and girls dash up the stairs hyped about a Sunday acting workshop: their ‘selection’ was by first-come-first-served online booking, rather than body type or ‘natural’ talent. For me, this isn’t just an exciting sight: it’s a wonder-ful one.

Nicolae Ceaușescu, Romanian dictator between 1974-1989

In his ‘Brief History of Puppetry’ lecture Byrne Power draws an interesting comparison between Nazi and communist censorship

the imaginary wall that separates actors from audience

I use this term interchangeably with ‘puppets’ but while in other languages puppet and marionette denote the same thing, in English a marionette is specifically the type on strings

talks on puppetry and the human brain (creative, pedagogical and therapeutic potential): Your Brain on Puppetry and The Most Powerful Tool in Education History.

What a luminous retelling of past and present beauty. I love the idea of art re-sewing the rags (and ravages?) of time. Puppets become puppeteers and memoir meets magic. Thank you 🪷

A wonder-ful, poetic evocation of present Romania and past Estella — or is it past Romania and present Estella. As you like it, and I loved it — thank you. A